Meet Steven Sasson: Tech Alum Who Invented The First Digital Camera

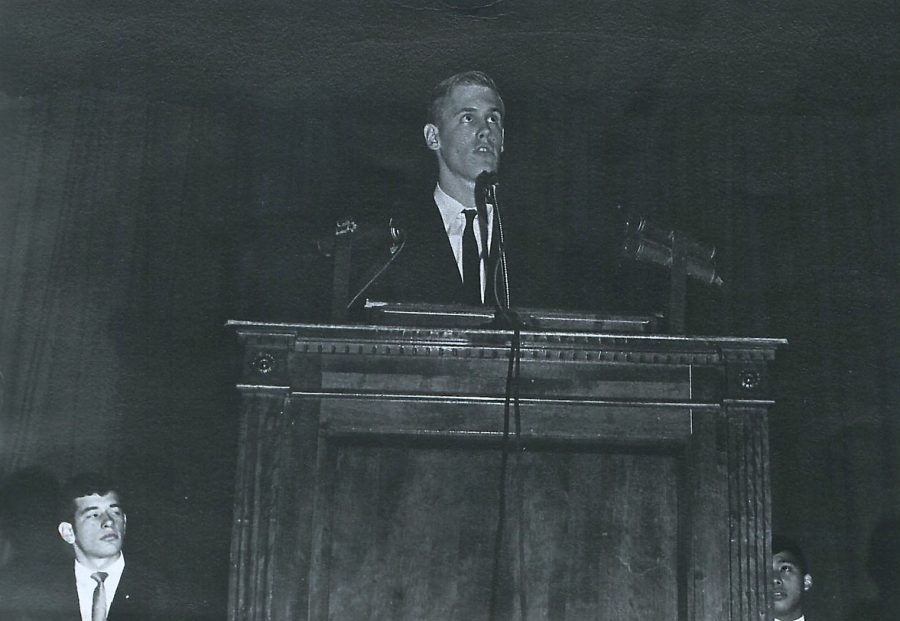

Steve Sasson giving a speech in Brooklyn Technical High School in 1968. As Longfellow president, Sasson addresses the student body with enthusiasm.

In 1975, Steven Sasson created the first digital still camera. Yet, before becoming an award-winning inventor, Sasson walked the halls of Brooklyn Tech.

Sasson graduated from Tech in 1968. He grew up in Bay Ridge and took the R Train to Dekalb Avenue to school every day. At Tech, he majored in College Prep and was the head of the Longfellows Club, an honor society that had a minimum requirement of 6 feet to join. He recalled, “Tech was a place where I could interact with diverse, accomplished students, and a place where I could take courses I couldn’t take at my local high school, like Shop in the foundry.”

Sasson was interested in electronics from a young age. As a child, he created small projects and experiments in his basement. “I started off with little lights and then graduated to amplifiers and then transmitters,” he mused. He would create these things with scraps he found around the neighborhood: “I used to get all my parts for my little projects by going around and picking up all these old televisions and radios people had thrown to the curb. I would drag them home and do autopsies on them.” He joked, “My projects would annoy people, smoke would pour out when the power supply blew up, and I would leave my junk everywhere.” The creativity and interest in technology that Sasson displayed as a child was fostered at Tech.

After graduating, Sasson went to Rensselaer Polytechnic in Troy, New York, where he studied as an electronic engineer. During his time in college, he became very interested in the effect of light on silicon, which became the subject of his thesis. This led to his first job out of college where he worked for Kodak, standing out as one of the few electrical engineers.

Sasson worked on several projects at the camera company, but it was a one minute conversation with a supervisor that changed his life. “I had just finished doing a lens cleaning machine that involved digital circuitry, and that was not something many people had done. So after, my supervisor came in and told me he had a filler job for me until a real one came along. He said you could either do a modeling of exposure controls for XL movie cameras, or you can analyze this new type of imaging device called a charge-coupled device. I jumped immediately at this idea and began analyzing its performance.”

Sasson worked on several projects at the camera company, but it was a one minute conversation with a supervisor that changed his life. “I had just finished doing a lens cleaning machine that involved digital circuitry, and that was not something many people had done. So after, my supervisor came in and told me he had a filler job for me until a real one came along. He said you could either do a modeling of exposure controls for XL movie cameras, or you can analyze this new type of imaging device called a charge-coupled device. I jumped immediately at this idea and began analyzing its performance.”

Sasson began by attempting to get all the electronics around the minuscule chip of the device to work. His next step was to analyze their performance, which he did by turning the output into numbers. He needed to store the numbers, and came to a great realization that “the numbers correspond to the charge pattern and light pattern that was resident on the device, so essentially, [he] was taking a picture.” This led Sasson to formulate his idea for the digital camera. “If I were to build a camera, with no moving parts, all electronics, that would be cool. Plus, it would annoy the mechanical engineers which of course I’m from Brooklyn, so I liked it.”

During Sasson’s inventing process, he had little budget or attention. It was a modest effort between him and two others in a back lab at Kodak. Similar to when he was a child, he began by scrounging up parts. He recalled, “I went down to the used parts bins in the factory and pulled out lenses and things they didn’t want.” Even after creating the actual machine, his work was not done. He had to create a playback unit to actually see the images.

Sasson credited his time at Tech to some of his success during his inventing process. While Tech students now only have to take DDP for one year, Sasson was required to take Technical Drawing for four years. At the time, Sasson did not particularly enjoy the class. He laughed, “I didn’t mind it at first but you know, after the 3rd or 4th year, I mean how many isometrics can you draw?”

Still, he could not help but notice the influence it had on his career. “When I was doing the layout of the digital circulator, there were no tools of any sort at the time, so I had to draw all of it by hand. It had to be very detailed because there were thousands of connections and address lines you had to follow, so I ended up finding that I had used my technical drawing discipline to make very precise schematics going on for pages and pages for the digital camera.” This documentation was the backbone of his initial process. Sasson went on to say “That was a discipline I innately had from being tortured for four years with that stuff, which came in very handy.”

As his invention gained traction, Sasson had to begin presenting the camera. “What happens is when you’re in a big structure like Kodak, with lots of different layers of management, and I was probably one of the lowest of the low, they had to carefully roll it out. It had to start with small meetings in conference rooms, and me demonstrating taking a photo. Once one group experienced it, they would invite their bosses, then so forth,” he explained. Slowly but surely, Sasson worked his way up the ladder.

Sasson faced several challenges when trying to popularize his invention because it went against the industry at the time. He would refer to his invention at demonstrations as “filmless photography.”This was a poor choice of titles, given that he presented to an audience who had devoted their whole life to film.

“People asked about the ‘why?’ not the ‘how?’ They would ask, ‘Why do you think Mr. Sasson, a 25 year old unheard of engineer, have you created a better invention? Why would this be a good replacement for consumer products?’” He soon realized the ramifications of his invention.

To popularize his invention, he used analogies, relating it to the scientific calculator and computers — innovations that were widely accepted that were happening in the world independent from what he was creating. This gave an idea of what his invention was. He then used Moore’s law, which was widely credited, to predict when the consumer camera would first be made available, as well as its development. 18 years later, the first consumer Camera was made, and his invention grew worldwide.

One of Sasson’s greatest honors was being awarded with the National Medal of Technology and Innovation for the camera. The award was presented to him by President Barack Obama in 2009, 25 years after beginning a project that nobody was originally interested in. He recalled Obama joking with him about the camera: “During my presentation, he pointed to all the white house staff photographers, pointed at me, and said this picture better be good.”

Sasson’s Brooklyn Tech experience provided him with a broad background of touch points for technology, which enabled him to invent the digital camera. “If I was left to my own devices all I would do is play with circuits. However, as it turns out, if you go into innovation, you often have to solve problems in many different fields. So having that exposure to multiple fields at Tech allowed me to better react to the broad interdisciplinary challenges faced by an inventor. It gave me a unique background,” he said.

Annabelle Savio (she/her) is the editor for Features. Annabelle values the field of journalism because...