A Lack of Communication About Asbestos at Tech

Brooklyn Tech’s building opened its doors in 1933, at the height of the Great Depression, and at the dawn of asbestos use in construction.

Decades later, state and federal regulations consider asbestos a potentially serious health hazard linked to cancers and other diseases, with strict federal rules governing its treatment and removal in school buildings, as well as mandatory communication with the public about asbestos management in those buildings. Uncertainty about whether the New York City Department of Education (DOE) has properly followed these rules at Tech has left some in the building concerned and searching for answers.

Asbestos is a mineral used in the construction of many old buildings like Tech. Resistant to heat and corrosion, it was popularly used as insulation and fireproofing in walls, floors, and tiles. Although asbestos was linked to negative health effects as early as 1899, it was only in the 1970s and 80s that asbestos began raising public alarm. As a consequence, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officially banned it in 1989.

Asbestos is most dangerous in friable form–meaning it can dry into a loose powder that can be released into the air and easily inhaled. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), asbestos can cause lung cancer, asbestosis (the scarring of lung tissue from breathing in asbestos fibers), and mesothelioma (a cancer of a tissue that lines the lung, chest wall, and abdomen). Conditions like asbestosis and mesothelioma do not appear until years after exposure, making public awareness essential to mitigating health risks.

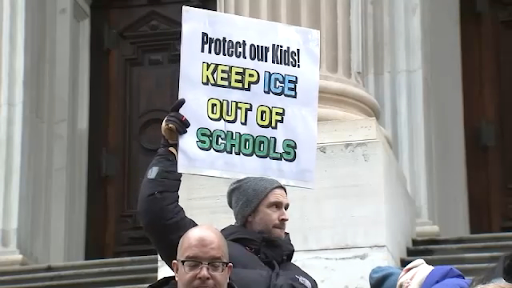

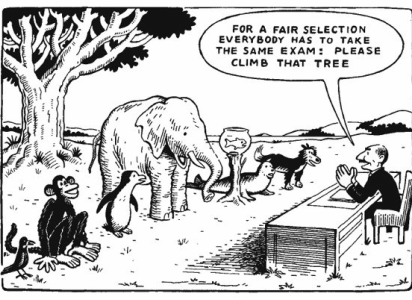

While the federal government does not often regulate environmental issues in schools, the EPA makes asbestos one of the few, underscoring the seriousness of the threat it poses. The Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA), enacted in 1986, requires schools to inspect for asbestos-containing building material, prepare management plans to actively prevent or reduce asbestos hazards, and provide yearly notification to parent, teacher, and employee organizations on the availability of the school’s asbestos management plan and any asbestos-related actions taken or planned in the school.

Some at Tech are concerned that federally required notifications about asbestos in the building are not reaching the school community. Mr. Avery, a social studies teacher, said, “To the best of my knowledge, the DOE is not notifying students and parents [about asbestos removal], as dictated by federal law. Neighbors around Brooklyn Tech got the letter about asbestos removal, but not Tech students, parents, nor teachers.”

In recent years, concerns about asbestos have been raised by teachers like Mr. Fine, a social studies teacher who taught for years in classrooms that contained asbestos, having had his classroom closed due to the presence of asbestos three times over the last four years. “In Fall 2019, the custodian warned that my room contained asbestos,” Fine explained. “They had to get the room cleaned up. But last year, a box containing asbestos broke open and my AP had to shut down the room. Now I am not in the room, but I know my room has issues, and trying to get answers was an issue.”

Amid all the ongoing construction on the building, Brooklyn Tech’s neighbors also have concerns about Tech’s asbestos issues after receiving notifications from The New York City School Construction Authority (NYCSCA) that have not been provided to the school community itself.

Darcy Miro, a mother of four who lives across the street on Fort Greene Place, received a notice about the asbestos abatement at Tech that was not particularly informative. “There was an initial single sheet of paper sent out [on asbestos abatement] and it wasn’t very thorough,” Miro said. “That was some years ago, and communication since then has been sparse.”

NYCSCA’s last letter to Miro in January 2023 stated that asbestos found in current construction work on Tech was non-friable (not consisting of airborne fibers), and that “the material is wrapped and contained before being disposed of by a licensed asbestos abatement contractor who is performing the asbestos removal work when the school is unoccupied.”

Miro, however, remains concerned as she and her family live through Tech’s ongoing construction projects. “For the asbestos abatement, they put it in a dumpster with a chute.” Miro continued. “You can see a poof with debris going every time they send something down the chute. We have no idea if that is asbestos or not.”

The NYCSCA’s letter further assured Miro that a third party would conduct air sampling required by New York City and the state, and that “once clean air requirements are achieved locations can be re-occupied.” No further communications have been forthcoming from NYCSCA.

The DOE’s apparent lack of AHERA-mandated communication with those inside the school has denied staff, parents, and students critical awareness about where potentially dangerous asbestos exists, and whether it is being actively abated.

Mr. Duncan, a physics teacher and leader of Tech’s chapter of the United Federation of Teachers, acknowledged, “We didn’t get any notification on asbestos removal from the DOE. Awareness is part of prevention, so we need to be aware of where asbestos is in the building.”

Principal Newman, who plays no role in AHERA compliance, responded to these claims. “The notice is supposed to be issued by the DOE to parents, students, and staff,” Newman explained. “I have not received the letter. But, every time the DOE does a project or abatement, I do get it, but I get a lot of those. But, they are not the official letter by the DOE, so I don’t send them out. I could send it out, I just have to check it with the DOE.”

Federal guidelines state that the asbestos notification requirement for Local Education Agencies (LEAs) like the DOE can be satisfied in one of three ways: by inclusion in the student handbook, by mailing a letter to each household, or by placing an ad in a local paper. No evidence of any such notification exists for Brooklyn Tech.

As a safeguard, AHERA also mandates that schools maintain an on-site log book detailing all asbestos inspections and abatement in the school building. In Brooklyn Tech, that book is located in the custodian’s office, in room 1E24.

“There is an AHERA book maintained in the custodian’s office that logs every asbestos-related job,” Mr. Newman said. “I believe by law, anyone is allowed to go to the custodian and sit down with the book.”

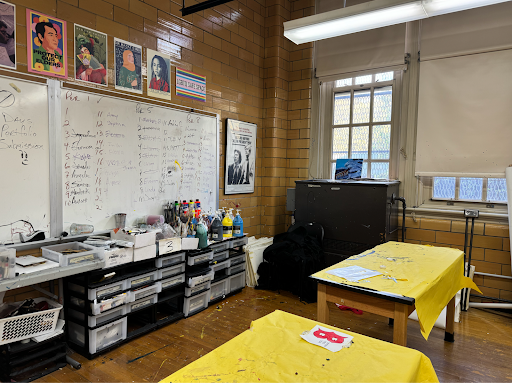

Mr. Morgenroth, a math teacher, reported possible asbestos around a 25-foot pipe in one of his classrooms in the fall of 2022 that was subsequently confirmed and required treatment. Having gained supervised access to the AHERA book with a limited ability to interpret its contents, he elaborated on the book’s purpose. “For safety and due diligence, the school keeps a record of where asbestos is located throughout the building,” Morgenroth explained. “Based on my understanding from the EPA website, for safety reasons, staff, students, and families are granted access to the information and asbestos management plan contained in the AHERA (book) so that we know where the asbestos is located and not to inadvertently disturb it.”

The AHERA book allows anyone to see where all dangerous asbestos is located in the building, and what efforts have been taken to control any health risks associated with its presence or removal. The book is a vital, federally mandated resource for staff, parents, and students, but access to the book has proven complicated at Tech.

Mr. Fine said that he tried to view the AHERA book, but was denied.

“I asked to see it [the AHERA book],” Fine said. “So, I made an appointment. On the day of the appointment, I went in with the union representative, Mr. Duncan, and they told me that I couldn’t see it, only Mr. Duncan could see it. So, I had to tell Mr. Duncan which rooms I wanted to see.”

Mr. Duncan, who was able to take a look at the book, said “I was able to get access to the AHERA book, and yes, there were some concerning things. The AHERA book contained all types of asbestos in the building. I am not an expert on asbestos, but there is asbestos in pipe insulation and under the floors.”

“Asbestos should be contained similar to a cast,” Mr. Duncan continued. “So, that it shouldn’t be airborne.”

But some of those casts may be failing. “A lot of asbestos in the building is treated,” explained Mr. Morgenroth. “That means it is contained, but not removed. My layman’s understanding is that those casts don’t last forever so if someone bumps into a pipe with an old, disintegrating cast, the asbestos could get out and become airborne.”

To keep close tabs on the state of asbestos in the building, AHERA regulations also require that school buildings be visually inspected every six months, and then reinspected more thoroughly every three years by a New York State Certified Asbestos Inspector and Management Planner who “must look at and touch asbestos containing material to assess its condition.” The findings of all inspections are then to be recorded in the AHERA book, making it an invaluable source of information to which access is essential.

AHERA mandates that the DOE provide parents, teachers, and employee organizations with consistent updates on asbestos in the building, yet the DOE does not seem to be complying, leaving the Tech community in the dark about serious health risks. Some at Tech even wonder if there might be a linkage between asbestos in the building and a number of cancer cases among long-serving staff members. Only the transparency and awareness that AHERA is meant to provide can address these kinds of concerns.

The Survey has reached out to request an AHERA book appointment and was told to follow up later. The Survey also reached out to the DOE for comment but has received no official response as of the publishing of this article. Updates will follow as reporting on this story continues.

Edward Zheng (he/him), is an editor for the opinion section of the Survey. Edward believes that great...