Although scaffolding obstructs Brooklyn Tech’s building all around, above it stands a 420-foot radio tower, housing the now defunct NYC Department of Education radio station WNYE-FM, the tower being over two times the height of the building.

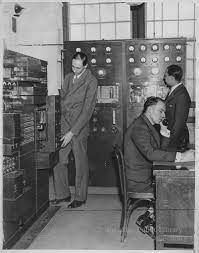

The tower was built in 1939, and before going out of commission in the 1990s, students and staff members pioneered the Department of Education’s radio operations, hosting the original studio and transmitter that was used before being relocated in the 1970s. Throughout the tower’s usage, various projects were completed, and opportunities were available for students to participate in programming at the station, which was part of an effort to promote work experience before students entered the workforce. Later on, topics expanded to include community interest and adult learning.

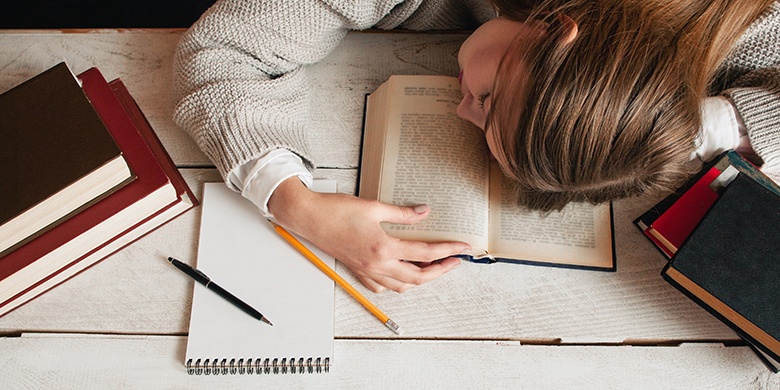

According to George Cuhaj (‘77), Tech alumni and archivist, one of the projects that Tech ran into the 80’s “allowed students who were unable to attend school classes to keep up with coursework, and was mostly for elementary or junior high school [level] students.” The broadcasts were an early form of remote learning that relied on radio broadcasts from to students could tune in.

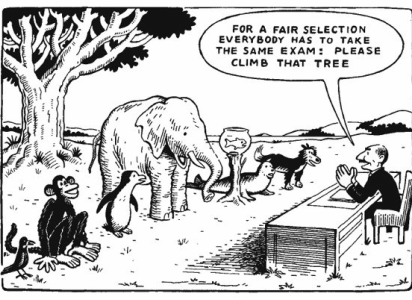

Similar to courses at Tech, the tower allowed students to learn the basics of a real-world job, aligning with the Techs’ founding mission to create “a better trained technical workforce.” Another notable activity of the tower was to air a monthly report by mayors, such as Fiorello La Guardia, using Tech’s radio station.

The first radio tower at Tech’s current building stood at 350 feet, shorter than the current 420-foot one, making the building and tower combined into the largest structure in Brooklyn up until 2015 with the construction of The Hub in Downtown Brooklyn.

Since its closing, there has been much curiosity among students and staff about what the tower is used for today. Principal David Newman explained “[the radio tower] is just a metal structure that has a flashing bulb so planes don’t hit it,” with work still being done by Tech to follow lighting requirements set by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The FAA states that “all structures exceeding 200 feet above ground level (AGL) must be appropriately marked with tower lights or tower paint.” Therefore, Tech must have a contractor on hand to climb the ladder and replace lighting on the tower yearly.

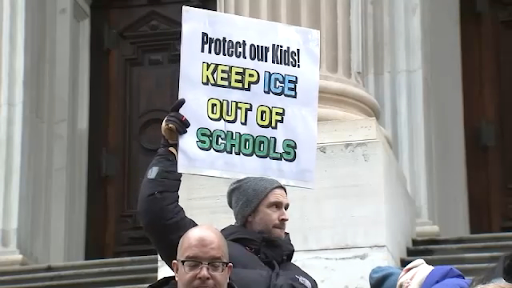

While the exact reason for its being shut down is not clear, Newman noted that it was partly due to health concerns stemming from exposure to radio waves. “From what I understand, somebody determined at some point that having an active radio tower on top of kids’ heads was not a good idea.” However, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which regulates radio, satellite, and television communications interstate and internationally, believes that “there is no reason to believe that such towers could constitute a potential health hazard to nearby residents or students.”

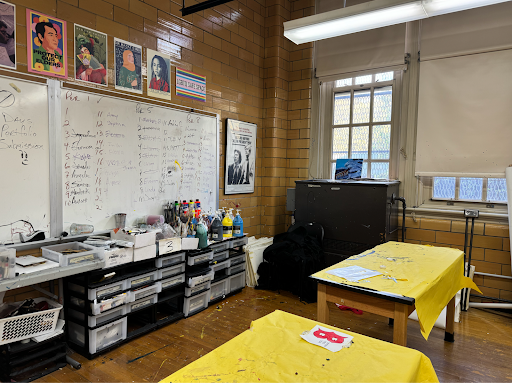

Since its final broadcast, the radio room, situated on the 9th floor, has been sealed off. The radio equipment has been dismantled, essentially leaving the room abandoned. Tech, however, has plans to repurpose the space as a recording studio for the music department. The radio room is just one of the former school facilities, alongside the foundry, for which the school has big plans. Due to how iconic the radio room is, many members of the alumni foundation are in support of bringing its legacy and use back to life.

Edward Sankowski • Jun 27, 2025 at 1:26 am

I did not know until now that the radio station broadcasting from BTHS was gone. I was initially a little sad, but only briefly. Situations change. I graduated in 1963! I was a participant in some classes involving a few other students in each class and a teacher. Interesting experiences. We did classes broadcast to students around the city. I feel nostalgia about it, and my time at Tech. I eventually (pretty soon) became a philosophy professor, which I still am, at a university in the Southwest.

Kenneth Hunold • Feb 23, 2025 at 8:24 pm

This is a great article that remembers a time when WNYE was a key part of the Board of Education’s broadcast strategy. I was also a student who participated in the broadcasts of the High School of the Air, and also the WNYE All-City Workshop, which produced radio dramas for the school system. That stint from 1969-72 led, almost directly, to a 50-year career in radio and TV broadcasting.

By the way, the radio studios and transmitter were on the 8th floor of Brooklyn Tech, not the 9th floor.

Ken Hunold ’72

Steve Hamburger • Dec 25, 2024 at 9:17 am

I was fortunate to be a student of Mrs. Goldberg in the fall of 1971 on HD of the Air. I display the small 3 x 5 service certificate in my office next to the MS and PhD certificates which were accomplished due to the incredible foundational education at Tech. BTW, my foundry nameplate still has important desk space prominence.

Kenneth Hunold • Mar 6, 2024 at 8:06 pm

I was also in the High School of the Air in 1968-1969, participating in the English lessons for home-bound students. I was also in the All-City Workshop that helped produce short radio dramas for grammar school students until 1972. In off-hours, I hung around the station and helped out with various tasks.

In 1969 I met Bruce Morrow (“Cousin Brucie” from WABC Radio) He was also in the All-City Workshop when he was in high school and came back to “guest star” in a production that I was also cast in. Through his help and some good luck, this led to me having a summer job at ABC-TV while in college, which in turn led to a 25-year career at ABC.

Perhaps during the next Homecoming celebration I will petition the Principal and Custodian Engineer to let me see the old studios. That facility has a surprising history in radio and TV dating back to 1938. It is a gem of a facility that was producing 1940s-style radio productions into the 1970s.

Tom LoMacchio • Jan 29, 2024 at 1:49 pm

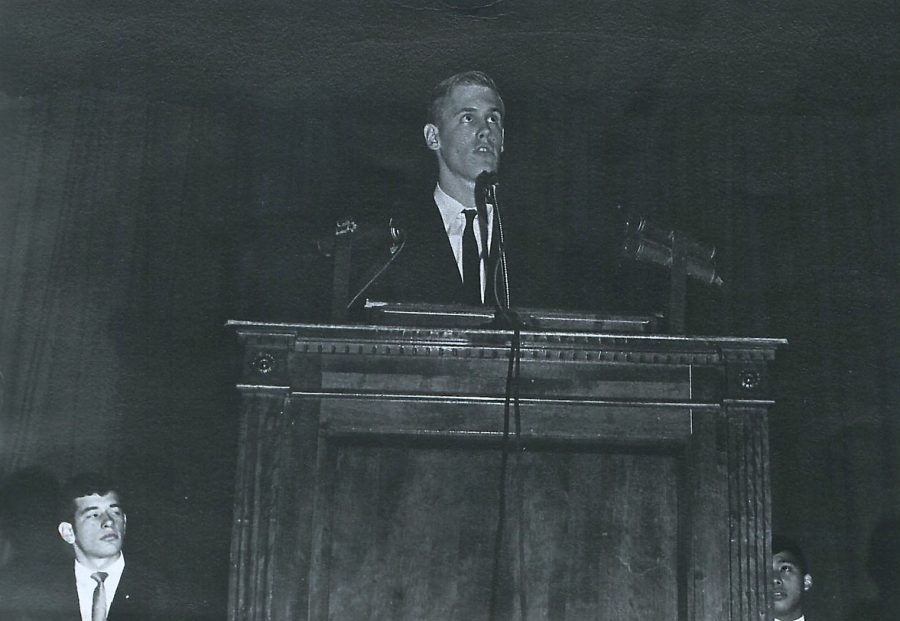

In my senior year, 1960 – 1961, I was one of a small group of no more than six classmates who were selected to take scholarship or honors English. I believe it was 7th Semester. Our teacher was Mrs. Horowitz, a kind and caring lady who guided us through the course material which included some readings in Shakespeare. The unique aspect of our class was that we would broadcast from the 9th Floor Studio over WNYE 91.5 FM on the “High School of the Air”. I seem to recall that we participated in two 15 minute broadcasts each week while sitting at a large wood rectangular table with Mrs. Horowitz at one end and two or three of us facing each other on the sides. In front of each student was a large disc shaped microphone on a stand that looked like it had been in service since the early 1940’s. Nothing was rehearsed. We had to be prepared as the answers we submitted to our teacher’s questions went right out over the air in real time. We had been told we were broadcasting to handicapped children at home long before handicapped accessibility. Unfortunately, I am unable to come up with the names of my fellow class members. I will always look back fondly on that relatively unique experience. Tom LoMacchio, ’61

Andrew Squicciarini • Dec 16, 2024 at 2:05 pm

I graduated tech in 1960, which was I guess a year before you did. My memories are kind of vague but I was in the broadcast engineering program that was offered at the time and we recorded the shows that were produced at WNYE. I think we originally recorded them on those upright Ampex console decks and then for some reason we archived them by cutting them onto vinyl records.

At the time I never really appreciated the education I received at Tech, wish I could go back and re-live it.

Andrew Squicciarini