Revisiting Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’—A Technical Marvel with Philosophical Underpinnings

I love science fiction. It is a true escape from reality. Good science fiction can strip away the complexities of humanity to its purest forms. It’s sheer imagination, sometimes greatly exaggerated and fantasized, sometimes rooted in realism and legitimate scientific thought. In general, the genre is absorbing.

That’s why I love “2001: A Space Odyssey” as a sci-fi classic.

I actually didn’t watch the film at first. I read the book. It showed up on my senior year summer reading list, the only sci-fi text to make it. As such, I burned through the pages. Finding myself confused by Clarke’s highly scientific, descriptive writing, I wanted to experience the plot visually. So, the next day, I watched the movie.

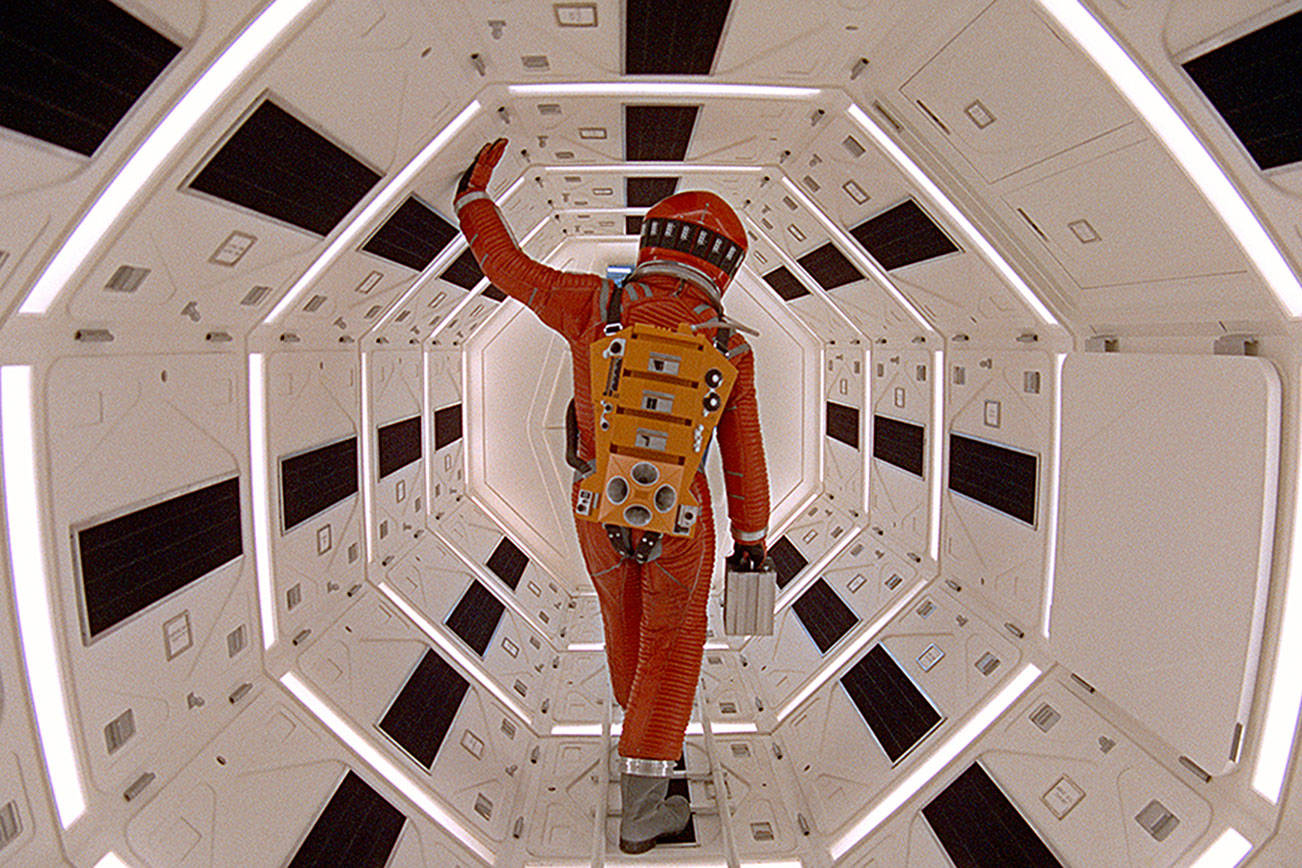

And, it was beautiful. Kubrick’s precise attention to detail and notorious perfectionism is on full display. To think that this was released before the moon landing is insane. It set the bar that even Ridley Scott said that every sci-fi movie following it was obsolete. Technically, the film is a marvel, by today’s standards and 1968’s standards.

Kubrick’s film is the exploration of mankind’s fullest potential. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), 1968.

Many of my friends who are into film criticism stopped there. And, I understand why. Yes, the film is a technical breakthrough, but it has little dialogue. It’s hard to sympathize with many of the characters. Ray Bradbury himself said that audiences would most likely not care for Poole’s death. The ending and beginning lack coherence with the main narrative.

Clarke’s Book Working in Tandem with Kubrick’s Vision

This is why I recommend to everyone I discuss this film with to read the book. Normally, I would scoff at the fact that one would need to read an entire 200+ page novel to understand a movie. But, in order to truly grasp the magnitude of the film, it’s worth it.

The book provides context, detail, wording, and imagery. I’d like to say that it guides the reader in how to think when analyzing and interpreting the actual movie.

Philosophically and allegorically, the film is about humanity in all its facets. The exploration of a godlike creator, scientific innovation, paranoia, emotion, social division, and evolution are central. This ties back to my point about how sci-fi strips complexities to its purest forms.

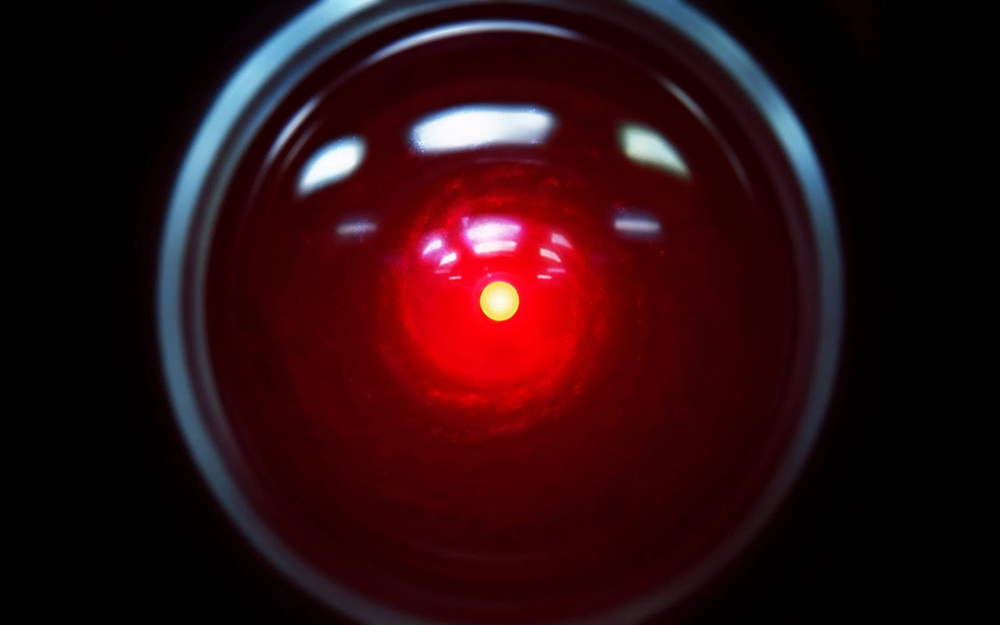

“A Space Odyssey” is rife with future conversations about human beings’ relationship with technology. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), 1968.

Nietzsche’s philosophy is very much in line with the film. Humanity is in its intermediate stages. Its fullest potential is far from being unlocked. Clarke explores that more explicitly in the book. He describes the main character David Bowman’s journey through the monolith as a rebirth of sorts, transforming him into the godlike Star-Child. It’s in line with the aliens that created the symbolic monolith itself. They became pure energy, godlike in a sense, after millions of years of technological evolution. The Star-Child is the first human to achieve its full potential.

HAL as a symbolic Representation of the Human Mind

Kubrick and Clarke also touch on artificial intelligence and technology. While the humans of the film exceed their humanity, the supercomputer HAL 9000 becomes increasingly human. Kubrick and Clarke use HAL as a symbolic representation of the human mind becoming increasingly bio-mechanical.

Humanity’s increased reliance on technology has provided society with wonders, but, at the same time, new ethical questions about the emotional interplay between humans and machines. The humans in the film discuss what to do with HAL, which emulates many of today’s conversations about self-autonomous driving for instance. The fact that Kubrick predicted these discussions fifty years ago is a testament to the legacy and impact of this film.

HAL’s paranoid breakdown is distinctly human. Roger Eggers described him as “the most human character” in the film despite his “perfect” computing abilities. The genius of Clarke and Kubrick is that they make you sympathetic to HAL comparable to Frankenstein or The Hunchback of Notre Dame. HAL made a mistake, like all humans have done once. Yet, that mistake cost him his “life.” His final pleas (*spoilers*) before Bowman disconnects him are saddening and remorseful, connecting the viewer’s humanity to the most artificial character in the entire movie.

Is HAL the most human character in “2001?” Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), 1968.

These allegorical symbols and interpretations “A Space Odyssey” are part of why I love this film. There’s a new angle or meaning every time I watch it. It makes you think, though not without getting confused.

Was Kubrick Being Pessimistic or Optimistic?

People constantly debate whether Kubrick is being pessimistic or optimistic about humanity’s future. Personally, I think he’s being a bit of both. Kubrick acknowledges the limitations of technology through HAL, that humanity is still far from its fullest potential, that any mistake could disrupt its equilibrium, causing the entire system to fall like HAL. Yet, he also posits what humanity at its fullest potential would look like through the Star-Child.

I think that Kubrick wanted to make a film that was simply human. Although that may sound unclear and cliché, the divisiveness over the film’s meaning is evident of that goal. We humans argue, and we also wonder about the future.

No film has made me think about the future as much as “2001: A Space Odyssey.” I’m a forward thinker in general, and the film connected with me because of that. I want to reiterate that this is MY favorite movie. It’s not the best movie ever made, nor am I claiming it to be. However, its impact on my thinking about technology and space travel is profound.

Ayaan Ali (he/him) is the Executive Editor of The Survey. He reveres the importance of journalism in...