Whether it’s in video games, movies, or gym classes, some sports get all the attention, while others stay off pop culture’s radar altogether. However, at Brooklyn Tech, teams like fencing, handball, and bowling are passionate pursuits that bring in competition wins and acclaim from all corners of the city.

Niche sports provide qualities that aren’t as well represented in their mainstream counterparts, whether it’s the lightning precision of fencing or the leisure sports allure of bowling and handball.

However, their small communities can make these sports more difficult for athletes to discover and join. “Being such a small sport entails that people are not going to know that you exist sometimes,” said Valentina Wolfe (‘25), a co-captain of the Girls Fencing Team.

Fencing

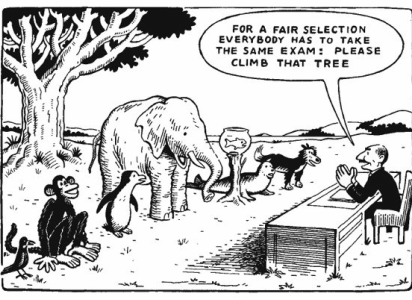

The small size of Tech’s fencing teams often limits their acknowledgment among the student body. With Tech sports teams such as track and field averaging 50 players, its total of 32 fencers across both rosters seems tiny in comparison. There are 15 players on the girls team roster and seventeen on the boys, and each team splits even smaller into two disciplines or weapons: épée and foil. Often, prior experience and private lessons outside of school are necessary, given the time and funding constraints of training a brand-new fencer from scratch. The team has especially struggled to afford the resources necessary for members to practice properly.

“We only got painted fencing strips down last year, and before that, we had to tape down our court every game,” said Wolfe, speaking about the bounds, or piste, of a fencing playing area. “It gets really frustrating when you see all the other teams have equipment, but everyone on our team has to buy equipment ourselves.”

Those personal equipment needs can get expensive for fencers and their families. Starter kits and necessary equipment, such as uniforms, gloves, masks, and blades, can go for hundreds of dollars, with lessons outside of school costing hundreds more. “In terms of us having extra gear and supporting girls who don’t have money to do the sport, but want to do the sport, there’s just not enough,” says Aisha Mowla (’24), a co-captain of the Girls Fencing Team.

Despite the practical obstacles, the fencing teams have proved their ability to succeed on the court. The Girls Fencing Team ranked first in their division and made it to the Public School Athletic League (PSAL) City Championships in the previous season, with the foil team placing third. The Boys Fencing Team is on another good run, finishing within the top three in the city this year. However, as a small team, they must keep in mind the legacy they’re going to pass down. “The majority of our team are junior and senior fencers, so it’s that aspect of ‘who’s going to be there after we leave?’,” said Wolfe.

Fencing has a strong culture within New York City, with many of Tech’s fencers belonging to clubs outside of school, but outsiders are not usually aware of it. While most have an idea of what fencing looks like and have even watched it in the Olympics, the common perception of the sport is that it’s elitist. This belief is often due to the expenses of the equipment and lack of tradition in the U.S., as most people do not grow up playing and are not naturally introduced to it through youth leagues or popular media.

“Both equipment and lessons are expensive, but the stereotype of it being a rich person sport is not always true,” countered Tristan Kuper (‘24). “I’ve picked up extra shifts [at work] to buy extra gear and a lot of my friends on the team are not rich people. Especially in New York, as it’s so diverse, it’s not only targeted to people who are more wealthy.”

Organizations like the Peter Westbrook Foundation, which brings opportunities for fencing to underrepresented communities across NYC, are also pushing to make the sport more accessible. Through efforts such as these, the fencing community will continue growing and becoming more diverse as new athletes are introduced to it.

Handball

Recently, the Boys Handball Team has had quite a run, making it to the finals last season, and winning the City Championship the previous year. However, it has the extra challenge of completely rebuilding for the next season, with nine out of the eleven members on the small team this year being seniors.

“I feel like it’s just going to die soon, but we’re still trying to make the best of it,” said captain Justin Chong (’24). “We always try to work with the new players and get them to work on their skills. I learned from my upperclassmen and that’s how I got better, so I just feel like we pay it forward and hope we get new recruits.”

Despite handball’s ubiquitous presence in European countries like Denmark and France, the game has not achieved as much notoriety in the United States. However, its fast-paced and team-centered elements make it a sport primed for popularity, especially within the casual pick-up game culture of NYC, where handball has roots dating back to 19th-century Irish immigrants.

The accessibility of the sport has also contributed greatly to its presence in NYC. “A lot of times in the parks growing up, you didn’t have hoops or some hoops in the parks were broken,” said Handball Coach Elmer Anderson. “You had to figure out other ways to entertain yourselves, and there’s always walls. The handball courts tend to have been a place where everybody would participate in playing.”

Handball’s community remains competitive in the city, with over 100 PSAL handball teams and the New York City Team Handball Club still going strong after 50 years. Even with the robust handball community in NYC, there are still concerns about the sport’s future. Anderson noted, “It’s changed a little bit, in a sense, where it’s not as popular as it was in the past.”

Chong encourages potential recruits to chase handball glory. “It might look like it’s hard or a little boring, but like every sport, once you get into it, it can be just as fun,” he said. “The competitive nature of it is pretty intense and … getting to the finals and seeing so many people there—it’s just really memorable and I feel like everybody should experience it.”

Bowling

Though bowling is an activity many grew up enjoying as a weekend pastime, few recognize it as a sport. “I don’t think people realize that it’s a sport that you can do,” said Coach Sigona, who has led the Boys Bowling Team for the past three seasons.

The Girls Bowling Team at Tech, with 25 bowlers, is the largest in the city, an often frustrating anomaly when it comes to the lack of competitors within PSAL. “You see fewer people, so I’d say that’s a disparity,” expressed Victoria Przydanek (’25), a member of the Girls Bowling Team. “Tech has the largest girls’ team… and if every school was like that, there would be more competitors and more emphasis for more schools to create their teams. Competing against each other would be even more fun.”

However, the Boys Bowling Team’s roster has only 12 members. “Because the school year starts so quickly, you don’t realize how many opportunities are available to you,” said Sigona. “I think bowling as a sport in general is not as popular as it was in the past. And I feel like that has a big impact on students finding out.”

Bowling is another sport in which members respect an individual and self-motivating playing style. Przydanek reflected on what makes the sport unique to her. “[Bowling is] self-driven and more [based on] self-analysis because it’s not like your performance is impacted by your team members,” she said. “It’s focused on you and how you’re doing that day.”

With the alley set-up and equipment required for bowling, venues are a significant aspect of how and when players engage with the sport. There are only six bowling alleys in Brooklyn and around 20 in all of New York City. At Tech, the bowling teams make their way to Melody Lanes in Queens. “Bowling alleys all over the city have closed in numbers,” noted Sigona. “Depending on where you live, [distance] is definitely a barrier to make it work.”

The bowling teams also share the challenge of passing down the legacy of the upperclassmen when dealing with a more niche team.”When one year has a lot of members, and the next year is way smaller, the skills don’t always get passed down or they halt, so the season varies a lot,” said Przydanek. However, the size and makeup of the teams of competitors mirror that of Tech’s. “Knowing that you can do the best that you can with the knowledge that your competitors are changing, as well, helps keep you on your toes,” she noted.

To members, it’s the community that is the biggest advantage of joining a lesser-known sports team. A small team means that players get to know each other on a meaningful level, each one sharing the experiences of the other. As Kuper expressed, “I like the camaraderie. Being that it’s small, you really get to know each other. It feels more impactful to do your part on the team.”