Why Queens Deserves a New Subway

Created by Gabriel Villanueva

South Queens commuters face a difficult trip when trying to get anywhere in the city. A ride into Manhattan can take upwards of an hour and a half, while a ride from one side of Queens to the other can take upwards of two hours. Anyone trying to reach the Rockaways has to either try their luck with a half-hourly Far Rockaway-bound A train or crowd onto the Q53 bus. This is why the Queenslink needs to be built.

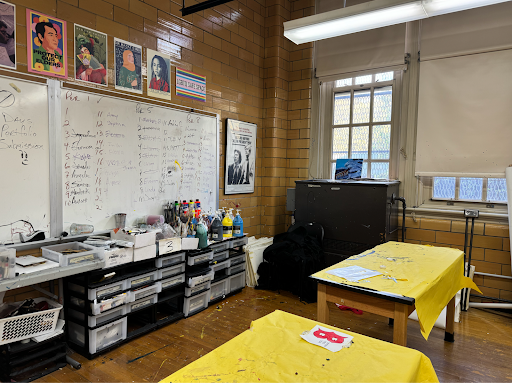

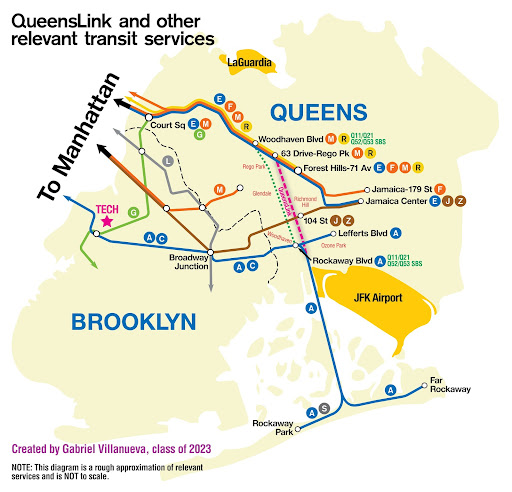

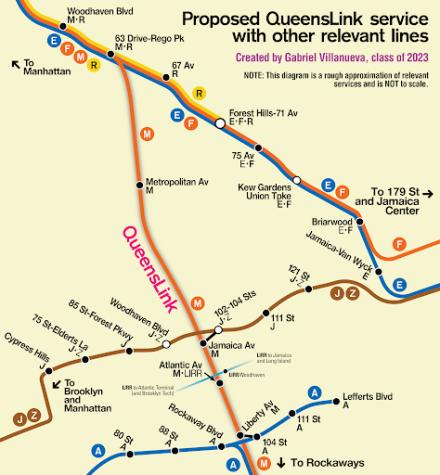

The Queenslink is a project that is gaining momentum in the transit community but has yet to receive any funding or city support. Andrew Lynch, the Chief Design Officer of the Queenslink, described the project as “a transit open space by reactivating an abandoned rail line [LIRR Rockaway Beach branch] as a subway line with new park space along the rail line.” According to Queenslink’s website, the benefits of the project include more frequent service to the Rockaways and Ozone Park, a north-south subway connection in Queens, and new park space in Central Queens.

Queenslink’s potential improvements to public transit compelled 20 politicians to sign a letter requesting an Environmental Impact Statement, so that the city can further study rail reactivation. New York City Public Advocate Jumanee Williams, Queens Borough President Donovan Richards, House Representative Gregory Meeks (D-5), State Senators Jessica Ramos (D-13) and James Sanders Jr. (D-10), and Assembly members Joann Ariola (R-32) and Pheffer Amato (D-23) were among the politicians who signed onto the letter.

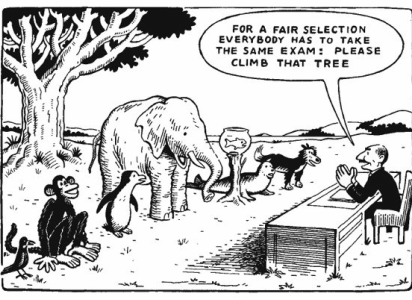

In 2019, the MTA released a feasibility study for reactivating the abandoned branch, projecting major benefits, but estimated the price to be $8.1 billion, or $2.3 billion per mile. By comparison, the Q train extension to 96th Street as part of the Second Avenue Subway project in Manhattan, cost $4.5 billion, or $2.1 billion per mile, ranking it as the world’s most expensive subway project.

However, the directors of Queenslink dispute the $8.1 billion figure for a number of reasons. Since underground infrastructure is not as dense in Queens as in Manhattan, the tunnels would not be as costly to build. Many transit advocates pointed out that the study inflated the Queenslink’s soft costs or costs outside of the construction like consultants and inflation. The MTA refused to release the study for a year, reflecting a lack of serious interest, leading Queenslink to release their own independent report which estimated costs between $3.4 to $3.7 billion.

Queenslink’s large price tag caused many city leaders to throw support behind the Queensway, a competing and cheaper proposal to convert the same space into an elevated park, like the High Line on the West Side of Manhattan. The Queensway has already gained the support of some politicians, including 2021 mayoral candidates Andrew Yang and Kathryn Garcia. Even though none of those candidates survived the primary, Mayor Eric Adams himself has followed suit and approved funding for the Metropolitan Hub of the Queensway. The Metropolitan Hub, near the intersection of Woodhaven Boulevard and Union Turnpike, is a proposal to offer many active learning and recreational spaces such as food concessions, batting cages, and bleachers by the Glendale ballfields; and space for temporary food stalls and a farmers market. We believe that the Queenslink is the superior project, and long overdue for the hundreds of thousands of commuters, including students, who live in Queens and Brooklyn.

The Queenslink would bring relief to Q52 and Q53 riders, as the Queenslink largely parallels those bus routes on Woodhaven and Cross Bay Boulevards. The Q52 and Q53 see upwards of 30,000 riders every day in 2018, rivaling ridership on the Q58, the most used bus route in Queens. Crowding on the two buses is exemplified during the summer when the two buses are the only option for the hundreds of thousands of Queens residents wanting to go to the beach. A train line could pick up those crowds and bypass all street traffic.

Moreover, Rockaway riders, who suffer one of the longest commutes in the nation, would see a much-needed service expansion that would double current capacity. Currently, the A train runs every 16 minutes to Far Rockaway, and riders wishing to get to Rockaway Park need to transfer to the shuttle. Queenslink would cut wait times in half, and building a more direct path through central Queens could shave 15 minutes off commutes from Rockaway to Manhattan. Rockaway riders won’t be the only people to benefit from the Queenslink. Re-routing the M on the Queenslink means the G can be extended to Forest Hills. This will upgrade capacity on the IND Queens Blvd Line (E, F, M, and R lines), one of the most used subway lines in the system while also giving Brooklyn Tech students a one-seat ride deeper into Queens.

In addition to transit benefits, Queenslink will deliver 33 acres of parks to Queens, which can be used for basketball courts and farmers markets. In short, the Queenslink is the perfect middle ground between train and park advocates, as it provides a train line with park space built around it. This would be a major quality of life improvement for the good people of Queens and all New Yorkers seeking out a tranquil place.

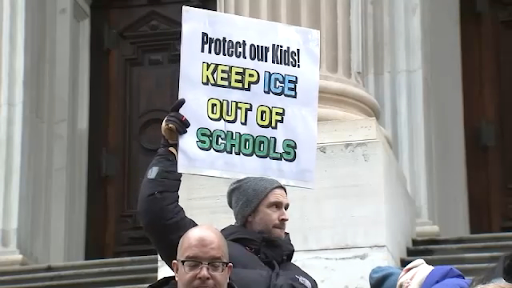

We therefore oppose the Queensway, not on the basis of the park, but what it represents: a prioritization of parks over much-needed public transit. Backers of the Queensway, like former Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe and the Trust for Public Lands (TPL), disdain public transit and are counting on the park to block any reactivation of train service. The Queensway website once stated that Queens did not need any new train lines, a stance that was eventually retracted when people pointed out that the subways in Queens are some of the most crowded in the system.

The act of using a park to obstruct train projects has happened before. In the 1970s, when the MTA was digging up a portion of Central Park for the 63rd Street Line, which the F train and LIRR use today, local residents protested, causing that project to stall temporarily and forcing the MTA to temporarily relocate a playground and significantly reduce the width of the tunnel. This delayed the project by seven years.

Another example is Atlanta’s BeltLine. The BeltLine, proposed back in the 1990s, is a similar proposal to the Queenslink, as it aims to build parks with transit. In the 2010s, the park portion of the proposal was built thanks in part to the TPL’s work, but funding for the transit aspect of the proposal is still subject to fights in City Hall. This shows that by building parks first, building rail becomes much harder and can be prohibitive.

Brooklyn Tech students largely agree with our support of Queenslink. Nayeem Khan (‘23, Mechatronics and Robotics), a student who lives in the Ozone Park/Woodhaven area, favored the Queenslink plan. “This might make sense because in order to go up, I have to take the Q10 bus. [With the Queenslink,] I will have better access to the J,” Khan explained. When asked about the Queensway project, Khan replied, “You don’t need no park, you got Forest Park.”

Noting the plan to build part of Queensway in Forest Park, Alexei Sanoff (‘25) said sarcastically, “There’s a big park in the middle of a railway, building a park in a park, what a useful use of space.”

Roberto Quesada (‘23, Environmental Science) who, like Nayeem, lives in a place that would be impacted by either project, prefers a subway line over a park. “Right now the only option to get from Ozone Park to Downtown Brooklyn is the A train which means that if there’s any delay, any issues on that subway line then you are basically stuck,” Quesada lamented.

The need to get to school on time has also led Jayden Ramkamar (‘24, Physics) to endorse the Queenslink over the Queensway. “It would be very beneficial for me. I would get to school faster instead of waiting 20 minutes for the A train,” Ramkamar said. “If train service was increased, trains would be less crowded,”

Given the overcrowded buses and the lack of access to northern Queens, Quesada and Ramkamar both reasoned that the abandoned Rockaway Beach branch should be leveraged to alleviate pressure. The activation of Queenslink would connect them, and Rockaway commuters, to the J and Z lines, which are isolated from the A train until Broadway Junction, approximately 4 miles away.

Tech students who do not commute from the Rockaways also shared their woes when faced with a lack of connectivity. “I definitely do think they should just make the line,” said Victor Kotchev (‘23, Mechatronics and Robotics). “There is no line from Brooklyn to Queens. You have to cut through Manhattan, and like I’ve always heard from my friends in Queens…from their house to Brooklyn to go to school is like an hour 30 to two hours.” It should be noted that there is a direct line from Brooklyn and Queens, the G train, but it suffers from long wait times and frequent weekend service changes that make it an unreliable choice. Even with proposed improvements by the MTA, 8-minute wait times are less than ideal when your trains don’t reach Queens because of planned work.

Taking a historical approach to the plausibility of building Queenslink, Social Studies teacher Sean McManamon noted that New Yorkers already have the privilege of an expansive system but that there were also massive hurdles involved in creating it. “That is really amazing that you can go so far. You can go to beaches, go to all these places,” said McManamon. “What are the downsides of it? It’s an old system and the fact that it took them so much money to build the Q [to 96 Street] and it was so slow. It’s like, can’t we get things done quicker? Can we get modern upgrades quicker?” Queenslink seeks to modernize the construction of new rail lines while playing true to the city’s history of serving communities without rail.

Principal David Newman agrees the city needs better connectivity and endorses Queenslink’s dual aims for parks and transit. “Leveling something and building a park is surely a lot easier than getting a station out there, but that’s what the people need,” Newman said, “ I’m not saying people don’t need parks, but I don’t see a lack of parks in the city.”

New York City has learned that the key to the future of the city lies in its infrastructure. A well-connected New York can thrive economically, socially, and environmentally. Queenslink is a way to future-proof our city and prepare for commuters who wish to travel directly to, or exclusively within, the outer boroughs. If our elected officials and the MTA fail to adapt to the realities of a growing and shifting city, they are neglecting what the future of city commutes looks like.

Joshua Montes (he/him) is a staff writer for Hard News. Joshua realizes the importance that journalism...

Edward Zheng (he/him), is an editor for the opinion section of the Survey. Edward believes that great...