With the advent of ChatGPT and a subsequent flurry of chatbots across the internet, teenagers have discovered their next big technological obsession: Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Yet in contrast to previous and relatively harmless online trends like TikTok dances or Snapchat streaks, AI is rapidly changing the entire educational landscape, leaving teachers scrambling to figure out how to handle a new world where AI is increasingly an indispensable crutch for students.

A growing number of students across the nation have been turning to AI for help on their assignments, with daily teenager Chat GPT usage doubling from 13% to 26% between 2023 and 2024. One in five students who know about ChatGPT use it for their school work.

In the three years since its release in 2022, ChatGPT’s unprecedented efficiency has made it an overnight necessity for students. Simply type any question into the chatbox, and ChatGPT will answer it within seconds.

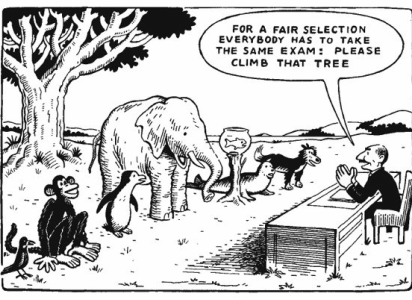

Students at elite schools like Tech, facing heavy workloads and pressure to succeed, can now turn students to ChatGPT for a shortcut. The versatile chatbot can solve math problems, write entire essays, generate images, and even imitate the prose of a typical high school student to deceive teachers suspicious of plagiarism.

“I think it’s just so normalized,” noted Maya Bugo, a senior in the Environmental Science major, adding that the phrase “I’m just gonna ChatGPT it” has practically become a verb of its own.

Students tend to use Chat GPT in two ways, either for blatant plagiarism or a more nuanced approach, where students ask the generator to summarize a text or explain a topic. AI’s proponents argue that it has enhanced and accelerated the learning process of difficult concepts.

“I’ve always used it as an aid to studying,” said one anonymous senior. “I basically ask ChatGPT what a topic is and analyze the response that ChatGPT gave me to fill in my homework. So I did use ChatGPT but I didn’t just copy what ChatGPT gave me directly to an assignment.”

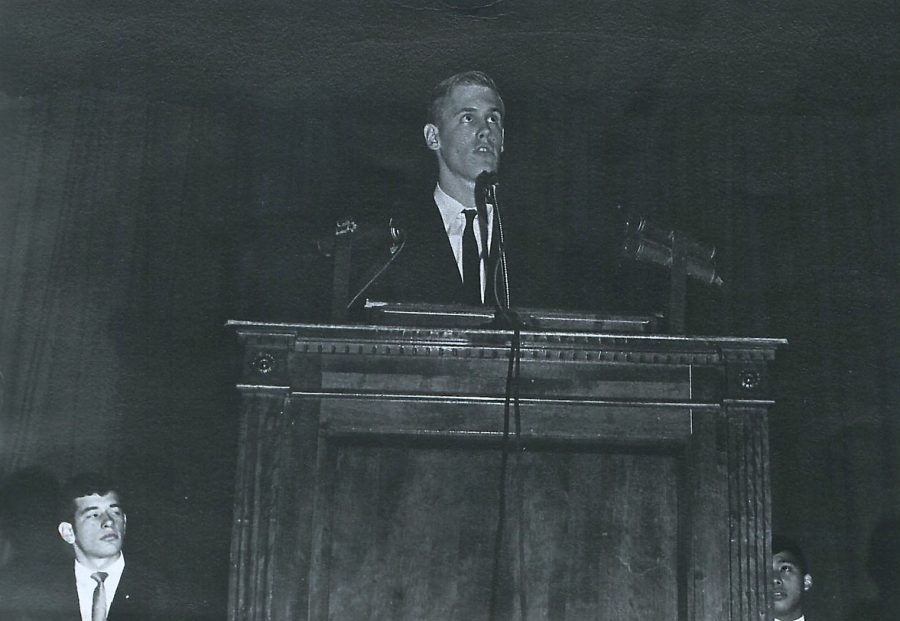

As AI use grows, emerging studies highlight its impact on learning. Matthew Jordan (‘25), a Law and Society major in the Weston Science Research Program, has been studying how ChatGPT affects student comprehension. His research involves three groups: one that copies answers entirely from ChatGPT, one that uses AI-generated content explanations, and one that completes work independently.

“For the cumulative exam, at the end of these homework assignments, we gave the students 21 multiple choice questions and a short response. For the results of the multiple choice, ultimately, the lowest scoring group was the group that copied things directly off of ChatGPT. They got a score of 190 out of 210, but the group that evaluated ChatGPT got an average score of 195,” said Jordan.

Jordan’s early findings suggest that students who engage critically with the material retain more information than those who complete their assignments entirely from AI-generated responses, but further experimentation is needed to draw conclusions.

A major concern for educators observing a surge of AI-dependent students is a loss of grammar and writing skills, leaving humanities teachers to play catch up with delayed students.

Another anonymous student reflected on how AI is disproportionately setting younger students back, saying, “I have not noticed freshmen using AI as much as in middle school. I noticed a lot of kids cheating using AI in middle school for their assignments.” Beyond a decline in essential writing and reading skills, many teachers are frustrated with AI-supported laziness and a lack of academic integrity, as well as the disregard for the humanities these uses of AI demonstrate.

Although generative AI is also used by students to answer math and science problems, this is nearly undetectable, unlike AI-generated writing. Many humanities teachers have turned to AI detection tools to promote fairness in the classroom. However, many students have reported unfair experiences with AI detection tools.

Amelia French (‘26), a Software Engineering Major, recalled a time when she was falsely accused of using AI. “My teacher ran all our essays through a sketchy AI detector,” she said. “If we got 10% or 20% above the threshold, we had to rewrite our essays. I was just 1% above the cutoff, and I had to redo mine. It was unfair.” Amelia noted that at least ten other classmates were also accused of AI use without solid proof.

Bugo, discussed alternative approaches, saying, “I really think it’s a personal measure, because my parents instilled in me that if you don’t understand [a topic], just keep trying at it. Don’t seek a cop out. Maybe an assembly could be held saying, ‘If you don’t learn this, then look at what you can’t learn in the future,’ or something like that. […] People are very worried about their grades, and I don’t blame them for that. If a student were to go to their teacher and tell them, “I can either turn this in with AI or could turn it in late, I don’t think a teacher should penalize them for choosing to do it on their own.””

Mr. Mike Miller, agreed with Bugo’s sentiment, explaining, “I am in grad school and I use AI to help me with my programs, but I will never submit code that was generated by AI.”

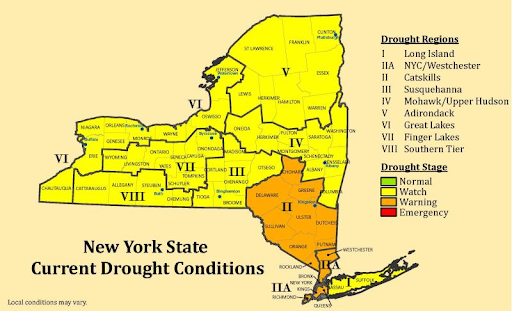

A final aspect of the AI discussion is its environmental impact. Each Google search that uses an AI snapshot “[consumes] approximately three watt-hours of electricity,” said Alex de Vries, the founder of a research company exploring the unintended consequences of digital trends. “That’s ten times the power consumption of a traditional Google search,” he added.

Resource demand is undeniably growing as AI is integrated into more fields.

As fossil fuel energy is used to generate the massive amounts of electricity needed to sustain AI data centers, most of which have cooling systems that use millions of gallons of water daily, AI’s environmental damage is doubtless. Although water isn’t a finite resource, it requires additional energy to be cleaned and recooled for the servers, and drives up local water costs. A computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, Emma Strubell, said, “In terms of the broader environmental impacts, water use for cooling the data centers and manufacturing the hardware is a big issue, especially because these things often happen in communities that actually do have limited water availability.”

Since 2020, Microsoft’s carbon emissions have increased by 30% due to the addition of AI services, despite a pledge to be carbon negative by 2030.

Bugo added that limited knowledge about AI’s environmental impacts isn’t the problem, saying, “The environment is able to deter some people from using it, but people just don’t care that much unless it benefits themselves.”

If a student wants to stop using generative AI in their education, whether for environmental conservation or due to ethical prohibition, complete AI avoidance is considerably complicated. Aside from Chat GPT, generative AI and other machine learning is being built into browsers, apps, medical devices, Siri and Alexa, facial recognition, cars, shopping websites, and beyond. Google, historically students’ go-to web browser, now features an automatic AI generated summary. This raises numerous issues, as information can be inaccurate, poorly cited or plagiarized, and reduces the need for students to exercise research skills.

As the AI industry grows more lucrative, and its services more convenient, companies of bots like ChatGPT like DeepSeek are rapidly implementing advanced features, and as the technological landscape shifts, it remains to be seen how classrooms, and students, will respond to this powerful tool.