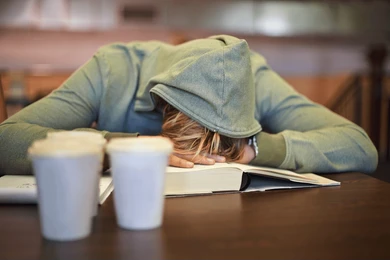

As Brooklyn Tech students flood into the school each morning, one can often hear the words “I’m so tired, I barely slept last night.” There’s barely a classroom without students drinking caffeinated drinks like Celsius, Rocky’s iced coffee, or Blank Street matcha. It’s no secret that Tech, alongside most other specialized New York City high schools, has an unhealthy and extreme culture of sleep deprivation, and has for a long time. Recently a new solution has been gravitated towards by Tech students: caffeine – and lots of it.

The Food and Drug Administration has not released a specific quantity of caffeine that is safe for teens, but Columbia University said that “until a safe amount is determined, if it’s impossible to avoid, people aged 12 to 17 should have less than 100 mg of caffeine per day,” the amount in the average cup of coffee. Columbia pediatrician Dr. David Buchholz and The American Academy of Pediatrics go a step further, saying stimulant-containing energy drinks have no place in the diets of children and adolescents, and that no one of any age, especially those younger than 17, should have energy drinks.

Yet Tech students do not heed this warning. In a Survey poll, over 50% of respondents reported drinking caffeinated drinks more than three days a week. 25% of respondents drink caffeine every day, or multiple times daily. For avid consumers of energy drinks, the daily 100mg limit is often exceeded, as not all caffeinated drinks are created equal.

The most popular pick at Tech is energy drinks, most notably Celsius, but also Arizona Energy, Bucked Up, Bang Energy, and Red Bull. These drinks can contain up to 300 mg of caffeine, as well as strong additives like beta thiamine, sucralose, and chemical stimulants. More natural options, including coffee and caffeinated teas like matcha, typically have less than 100 mgs of caffeine but are less prevalent at Tech. This doesn’t even begin to cover all the unintended caffeine many students consume in gum, chocolate, cereal, pre-workout supplements, and more.

Caffeinated drinks cost Tech students more than their health – both Biological Science major Karolyn Breen (‘25) and Civil Engineering major Brody Grace (‘27) reported paying over $20 each week for drinks, even though both prefer the cheapest options, like the energy drinks at Rocky’s Deli that cost just $1-3. Coffees and teas from popular spots nearby, such as Blank Street or Starbucks, can cost up to $8, which quickly adds up. In addition, students tend to consume more and more caffeine over time as tolerance grows, increasing health effects and financial burdens.

Caffeine has been used as essentially a band aid for a gaping and widely known problem of sleep deprivation in high achieving New York City high schools.

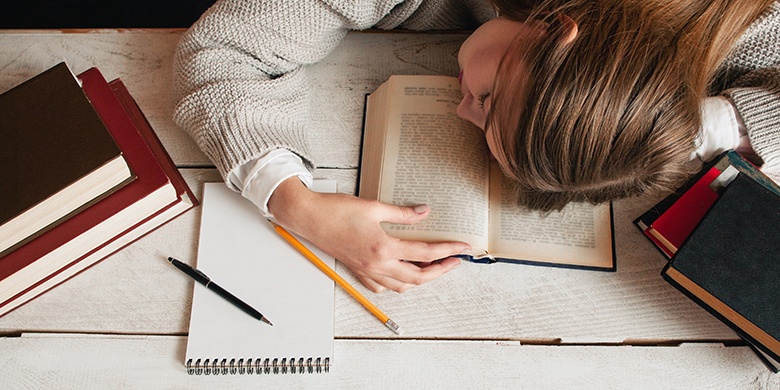

In a Survey poll regarding nightly sleep quantity, 90% of students reported getting less than the CDC recommended 8-10 hours of sleep per night for teenagers – significantly higher than the 77% national average for teens who responded similarly in the CDC’s own polling. Roughly one-third of Tech respondents reported getting less than five hours of sleep each night.

“I have observed that students at Tech tend to get less sleep due to their heavier workload,” said Ms. Zonia Adalat, an AP and Regents Chemistry teacher. “The demands of our curriculum can create challenges for maintaining a healthy sleep schedule. It seems that some students take on more courses than they can handle, which leads to overload.”

Students cited several reasons in interviews for their poor sleep, including schoolwork, extracurriculars, spending time with friends, and phone use. Repeated lack of sleep leaves students playing constant catch-up.

“[The expectation is to] do what you’ve got to do for homework, so sleep isn’t prioritized,” Brody Grace said of Tech’s sleep culture. “A lot of kids just sleep in class or in the hallways.”

Grace added that Tech students’ sleep patterns are “not great, especially compared to other schools where the work is less heavy or repetitive”, as he claimed it is on platforms like DeltaMath, a website popular in the Brooklyn Tech mathematics department. “It’s less pressure at those schools but more healthy for students.” Grace said.

Apathy towards sleep runs deep among Tech students, including Toluwalase Womiloju (‘27).

“Getting a good night’s sleep used to be so much more important to me, but it’s not anymore due to my busy schedule,” she said. “I now prioritize homework over sleep, and I have sports and a social life to try and keep stable. I try to go to sleep early but it just isn’t that important to me anymore.”

As students are often unable to get a good night’s sleep, they suffer a physical toll. When Tech students do not get enough sleep they feel “jittery and frazzled” according to Grace.

“I notice a visible difference in my appearance and also my ability to concentrate when I get a solid eight hours as opposed to the six [hours I get on weeknights],” added Breen. “When I get a bad night of sleep I’m typically very irritable and obviously tired. I have brain fog and I tend to zone out more in my classes.”

Ms. Adalat noted that lack of sleep can have enduring negative impacts on student well-being.

“In the short term, sleep deprivation can hinder academic performance, while long-term effects may negatively impact mental health,” Adalat explained. “From a scientific perspective, adequate sleep is crucial for student performance. Those who are well-rested tend to be more engaged during class discussions and perform better academically.”

Teachers feel concern and empathy for their exhausted students. Ms. Adalat shared that when she finds a student sleeping in class, “[she allows] the student to rest for a few minutes before approaching them to suggest they take a brief walk to help re-energize.”

Tech students reported getting a bit more sleep on the weekends in polling, but attempting to “catch up” on lost weekday sleep is not a viable long-term solution. Sleep debt is the difference between how much sleep you need and how much you actually get, as well as the cumulative effect of poor or missed sleep. Persistent sleep debt cannot just be paid back, and can have chronic health effects, especially in teens. Further side effects include inability to concentrate, poor grades, panic attacks, mood disorders, anxiety, depression, lack of inhibition and impulse control, thoughts of suicide and more. Further research found students who do not get enough sleep are more likely to struggle with concentration, problem-solving and retaining information, negatively impacting their academic performance and leading to lower grades and decreased productivity in school.

A recent study reported that the students who reported the most stable, consistent sleep patterns earned a .45 higher GPA of 3.66 that students with more variable sleep. Students with regular sleep patterns also reported higher levels of well-being, even when controlling for SAT scores and baseline happiness. Research overwhelmingly supports that sleep quantity is a direct predictor of mental stability and the amount of sleep that a student gets “is one of the strongest predictors of academic success.”

This research is no surprise to students.

“I know about [the effects of poor sleep]. I’m very aware it’s not good for you,” said Grace. “It just doesn’t fall very high on my list [of priorities].”

Regardless of the reason, students are still getting severely insufficient sleep. To compensate, Tech drinks caffeine, and lots of it.

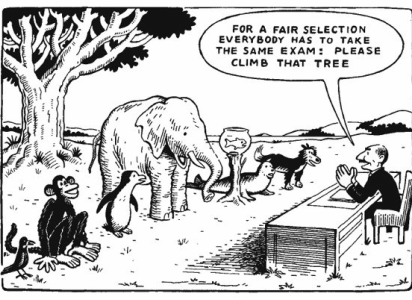

While all of these are persuasive reasons to try and get more sleep, that isn’t an option for many students. Tech is proud to have a high-achieving student body, but that often comes at a cost to the physical and mental health of students. There isn’t much time in students’ ambitious schedules to devote to better nights of sleep.

There are still things that students can do to get the benefits of good sleep, even if they are short on time. Put phones and laptops away as early as possible, leaving homework on paper for last. Avoid food or exercise late into the night, which can upset circadian rhythms. No matter how much caffeine is consumed, drinking it at least 10 hours before going to bed can significantly protect teens from trouble sleeping. Even these small habits can improve productivity, executive function, and mood.