Assessing the Flaws: Why It’s Time to Move Beyond Standardized Testing

Photo courtesy of History of Place

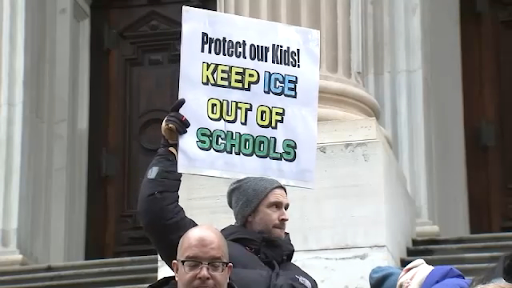

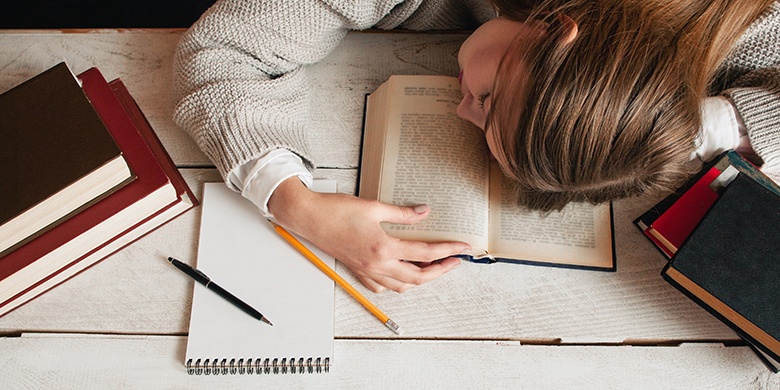

Standardized testing has become the culmination of a student’s education. Every year, students sit for hours-long tests to measure just how much material they have retained, as they vie for top scores to impress colleges and peers alike. Preparation for these tests spans much of the school year, and many students attend prep courses and take countless practice tests to get the highest scores possible.

There is a reason students devote so much time and energy to test preparation. Standardized tests have a tremendous impact on their future. The most consequential tests, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and Advanced Placement Tests (APs), are administered by the College Board and set the bar for competitive college admissions. The desire to score highly on these timed exams can drive some students to spend hours poring over test material and learning strategies to maximize efficiency.

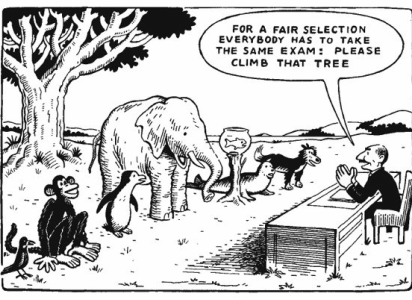

The sheer gravity of standardized testing derives from an inflated emphasis on test scores in modern education. Yet despite the weight it carries, the standardized testing model is highly flawed. To better assess students, the current system is in desperate need of an upgrade. Distaste for standardized testing among students and teachers alike is widespread and growing, largely due to the inherent inequalities embedded in it.

While one student may be an excellent tester who can memorize formulas, manage their time well, and thrive in the high-pressure testing environments, another may instead excel in lower stakes situations that require creativity. Naturally, some students will perform much better than others, even if they have an equal understanding of the material. The impact these tests can have on a student’s future makes this disparity all the more problematic.

“Just because you can’t perform well on an exam that has a three-hour time limit doesn’t mean that you don’t understand something,” Ariel Segura (‘27) commented. “It could just mean you’re not good at testing.”

This is partly why many colleges and universities have gone test-optional in recent years. As a result, students who may not score well on standardized tests like the SAT, but have diverse skill sets, are more willing to apply to prestigious institutions, as other attributes are allowed to shine through.

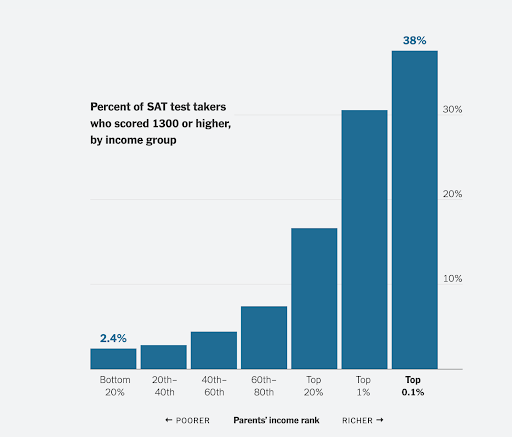

Socioeconomic inequalities are also exacerbated by the current standardized system. On paper, these tests are uniform and fair, but in reality, students from wealthier backgrounds often have the upper hand, as their families can easily afford expensive tutoring and prep to give them the best chance at scoring well on the most important exams.

One popular prep company, The Princeton Review, charges $364 an hour for their premier “SAT 1500+ Tutoring.” Another one of their courses, which promises a 1400+ SAT score, runs $53 an hour, which, while much cheaper, can add up to a hefty sum.

“The most glaring [problem with standardized tests] is that people in wealthier families will have access to far better resources and even tutoring to prepare for the exams,” argued Social Science Research major Nicolas Wiedemann (‘26). “If success in a standardized test hinges on wealth, it destroys the whole premise of being able to measure students’ capability.”

AP and Regents classes are also centered around preparing students for the big exams at the end of the year, often forcing teachers to place a demanding focus on delivering content instead of cultivating a more enriching classroom experience for students. .

As Wiedemann put it, when teachers are forced to structure their classes around the AP test, they are often restricted in what they spend time teaching.

“Individual teachers have very little choice over the content and structure of their curriculum, which I think damages the values of their classes,” he said. “We waste tons of time learning about the specifics of the College Board and the tests, and how to write things like DBQs.”

AP Language and Composition teacher Ms. Lisa Bensing is frustrated about the time ELA Regents prep takes from her class.

“We have to spend a minimum of a week of class time [preparing for the regents], which would be more beneficially dedicated to continuing with the course itself,” she said.

Ms. Bensing also lamented the mindsets of students taking AP Language who are more concerned with learning how to apply material to the test than thinking critically about content.

“It is a way of training students to think, [one] that values standardized testing, that values the pacing…and then devalues taking your time thinking, engaging with your peers in social situations and creative thinking,” Bensing explained.

The pressure to perform well on these exams also places an enormous burden on the mental well-being of students that can affect their ability to focus, process information, and manage their emotions, all of which can lead to poor academic performance and heightened anxiety.

Skepticism about the effectiveness of standardized testing has brought about the rise of the test-optional movement. According to the National Center for Fair and Open Testing, nearly 80% of US colleges will be either test-optional or test-blind for the Fall 2025 application cycle, meaning students can either volunteer their SAT scores, or have schools ignore them altogether.

AP exams have also undergone substantial changes. In the past few years, the College Board has initiated a “recalibration” of certain popular exams, changing how certain sections are scored. Using new grading rubrics, approximately 500,000 more exams would receive a passing score of three each year, alleviating some of the annual exam stress for students.

Despite its detrimental effects, standardized testing is not without its merits. The current standardized system makes nationwide student assessment not only possible, but extremely efficient. This is undoubtedly useful, considering how many standardized tests are taken each year. According to the College Board, 1.97 million high school students from the class of 2024 took the SAT, and over five million sat for AP exams.

Potential alternatives to standardized testing, such as Performance-Based Assessment Tasks (PBATs) in NYC Consortium Schools, promote project-based approaches to large-scale student testing, offering a flexible framework with no formal final exam. Rather, as the year goes on, each student develops a project that builds to an end-of-the-year performance-based task – projects may vary from lab reports on student conducted science experiments to oral presentations on original research.

To Segura, the usage of PBATS in Consortium schools seems needlessly cumbersome. “It takes one to two months to do them in the first place,” he said, arguing that “coming up with something that tests a kid’s ability and also has the same efficiency of being able to get everyone’s score within a few weeks is very, very difficult.”

Environmental Science major Elliot Phillopon (‘26) maintains that standardized testing gives students the opportunity to prove their academic ability.

“They are essentially a culmination of everything you’ve learned in a year and it’s useful to show you’ve done well in the class,” he said.

Still, standardized tests have inherent flaws, leaving many students – especially those economically deprived or inept at test-taking – at a disadvantage. The full range of a student’s capabilities, creativity, skills, and strengths simply aren’t measured properly through these tests. Though the alternatives may be inefficient and make comparing students more difficult, the blatant inequalities caused by the standardized system make the extra effort worth it.

While completely forgoing standardized testing would be unwise given our reliance on it, the education system as a whole should shift away from measuring a student’s potential completely on a test score and instead utilize a mixture of alternative methods in addition to standardized testing.