On March 20, President Trump signed an executive order to dismantle the federal Department of Education. The order instructed Secretary of Education Linda McMahon to “facilitate the closure of the Department of Education and return authority over education to the States and local communities.”

It is unclear what steps McMahon will take to shut down the department. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has already fired nearly half of the DOE’s federal employees. To completely close the department, however, would require Congress’ approval. Plans for a vote have not been announced, but McMahon said she will “eliminate the bureaucracy responsibly by working through Congress to ensure a lawful and orderly transition.”

Trump announced plans to delegate the main functions of the Education Department to different departments. The Small Business Administration (SBA) would regulate federal student loans, while special needs and nutrition regulations would move to the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), but the capacity of these departments to take on new roles is unclear. The DHHS recently announced layoffs of 10,000 employees, and the SBA has reduced its workforce by 43%.

The legality of the shift has also been questioned, as any major departmental changes made without congressional approval could be illegal. For example, the DOE’s distribution of Title I money, essentially funds given to the lowest-income school districts, was enacted by statute, so Congress would need to sign off on any modifications to the distribution process.

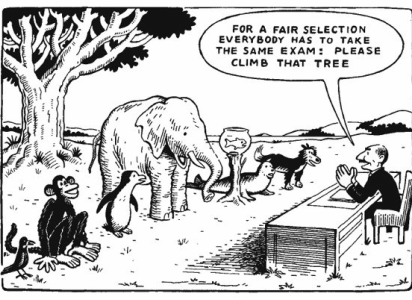

The true impact of a federal DOE dissolution could be far less dramatic than it seems. Aside from financial aid and special education funding, education is already largely localized in the US. Curriculum, graduation standards, enrollment requirements and the establishment of schools is the responsibility of states or communities.

The majority of school budgets also come from state and local tax revenue. Even schools with the highest percentages of federal support receive over 75% of funds from state and local budgets.

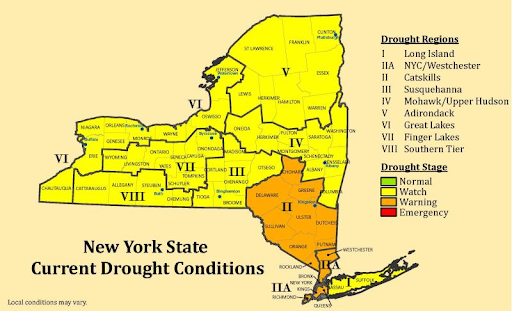

Mississippi uses the highest percent of federal funding of any state at 23%, while New York uses the lowest, at 7%. Still, Mississippi spends only about a third of what New York state does on each student. As a result, the loss of federal funding for a state like Mississippi is much more impactful than for New York.

“I think [federal cuts] will create disparity,” said Scholarship Coordinator Mr. Serge Avery. “There are states where departments of education are probably really underfunded. So New York, we’re…lucky.”

The federal DOE’s contributions to the NYC Department of Education budget are sizable, but only account for 5% of the city’s total budget. Losing federal funding and support for disabled or low income students would likely have a negligible impact.

“New York does not get that much from the federal government in terms of students with disabilities [but] other states do,” said AP of Special Education Mr. Jacob Brodsky. “I think that [moving special education under a different agency] would be a problem because certain other states…would have less oversight or less resources, potentially, or maybe their program won’t be funded properly.”

Whether the redistribution of special education responsibilities will affect students depends on whether any new iterations of the department will serve the same functions as before and how efficiently they are moved. At present, neither outcome can be determined until the administration announces its plans.

Also unclear is how the dismantling of the DOE will affect federal testing. Currently, each state is responsible for creating and administering their own benchmark exams, making it unlikely students will see much of a change.

However, the DOE is responsible for tracking national educational progress through the “Nation’s Report Card” tests, and it is uncertain who will do the work of collecting and analyzing these data without a federal education department.

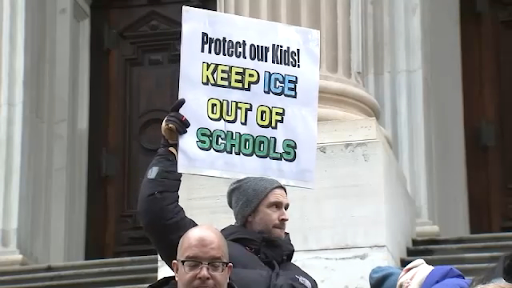

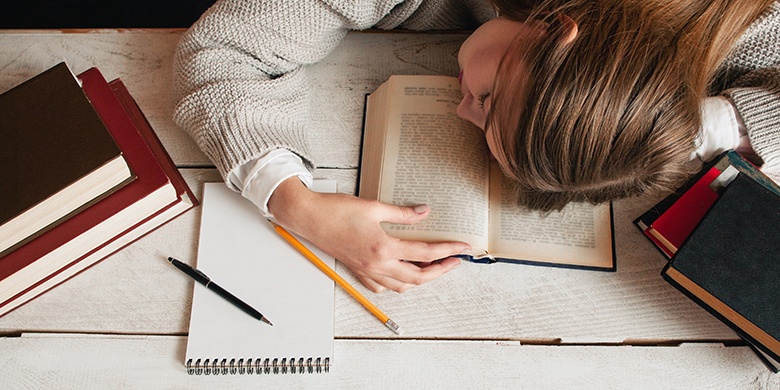

While responsibility for the department’s functions has yet to be redistributed, students have already experienced issues. On March 12, the FAFSA website broke down, just days after the DOE laid off the entire team responsible for supporting FAFSA technology.

“I don’t totally understand the rationale behind cutting the DOE,” said Mr. Avery. “I think there will be problems for FAFSA, financial aid processing, problems for Pell Grants. I don’t think it’s good news.”

In 2024, the federal government distributed almost $33 billion in Pell Grants, which are awarded to students who demonstrate “exceptional financial need” and are entering college as undergraduates. Unlike student loans, Pell Grants do not need to be repaid, allowing students to attend state schools for no, or next to no, tuition.

The Trump administration has promised to continue providing essential aid and loans, but has not explained how these will be distributed.

Mr. Avery does not expect the transition to be smooth, anticipating there will likely be problems if the administration shifts financial aid responsibilities out of the Department of Education, potentially creating problems for current juniors and underclassmen when they begin the college application process.

As with special education funding, a student’s ability to obtain adequate financial aid could become dependent on their state, depending on how much money a state has to administer grants.

“It would seem the Department of Education would be the best department to continue the process of financial aid,” said Mr. Avery. “Maybe the state will pick up the slack [but] I don’t know if they’ll have the money.”