A century ago, gaining admission to an Ivy League school was far easier than it is today. With no standardized admissions tests like the SAT or ACT, and acceptance rates for schools like Harvard and Yale hovering around 50-65%, the path to admission was much smoother. At the time, admissions were largely shaped by factors such as familial connections and the lack of any female applicants, limiting education mostly to wealthier students.

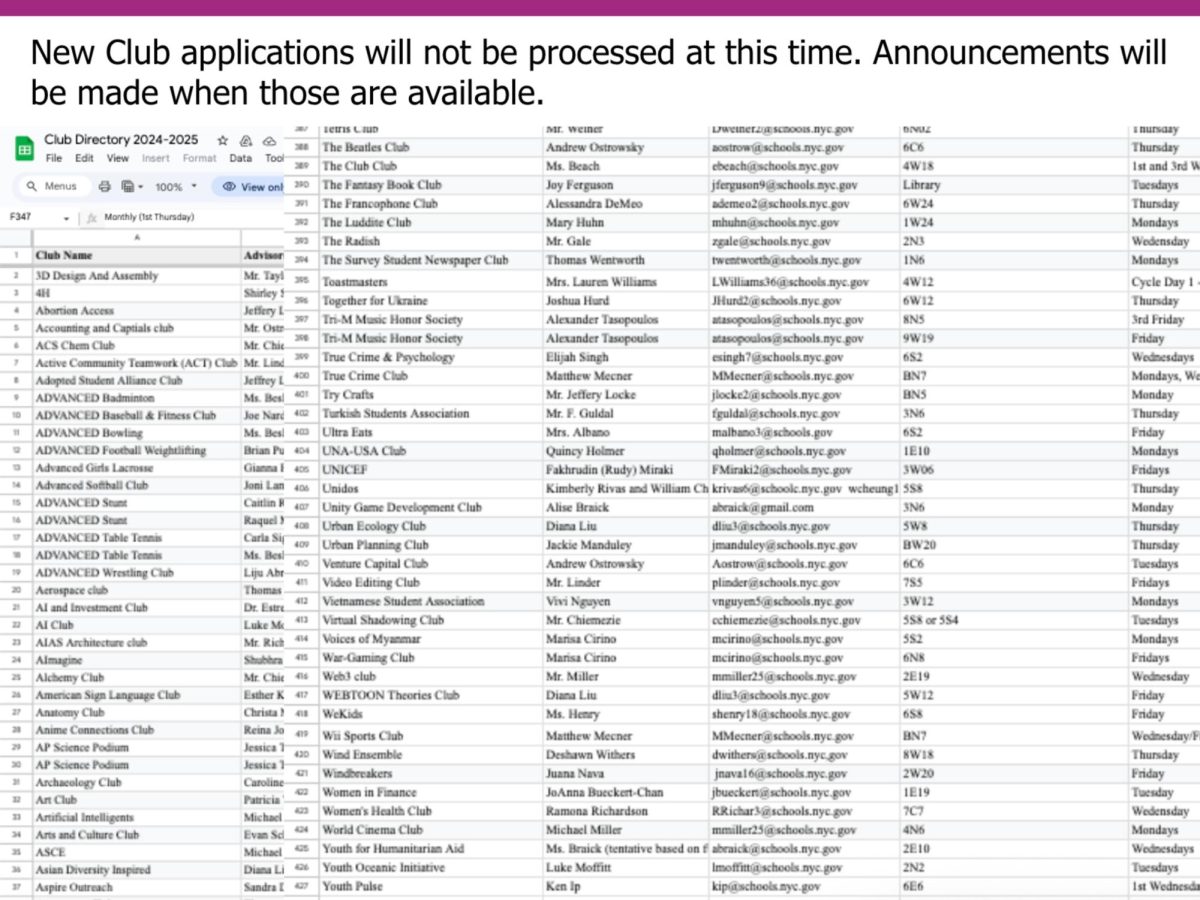

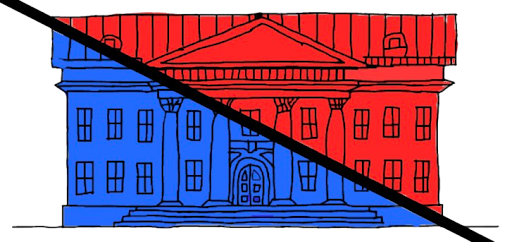

In the 20th century, as Ivy League schools opened their doors to broader groups of students and introduced other factors such as the SAT, the college admissions process changed forever. Today, acceptance rates for all Ivy League schools are under 10%, with hundreds of Tech students vying for only a few spots.

To understand this dramatic change, a look at the history of Ivy League admissions is necessary.

The first Ivy League University to be founded was Harvard University, then known as Harvard College, in 1636 – over a century before America gained its independence. During this colonial period, racial and gender segregation were deeply ingrained in every aspect of society. College was only for wealthy white males. Yale University was founded in 1701, and followed the same exclusive standards.

Additionally, only people with financial means applied to college. The applicant pool was limited, in part, because financial aid did not exist until 1958. There were a limited number of scholarships available, and most students were busy working to help their families to get an education. employers did not pay for their employees to attend higher education institutions.

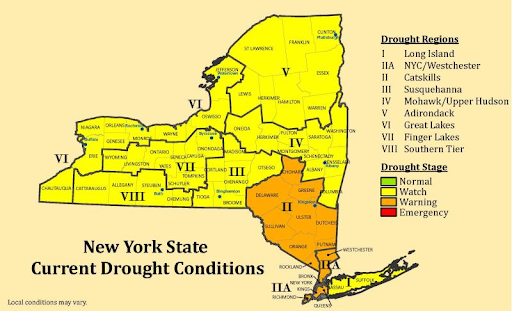

Since the number of people applying to university was so low, schools accepted almost everyone who applied. In the 1800s, only about 63,000 students attended university in the United States, but as of 2022, that number is almost 16 million. The majority of Ivies in the 1800s had a 100% acceptance rate, while some had slightly lower acceptance rates, like Princeton, which had a 95% acceptance rate in 1860.

Grades and academic achievement were essentially not factors in applications. If a white male applied to an Ivy League and could afford tuition, he was almost guaranteed acceptance.

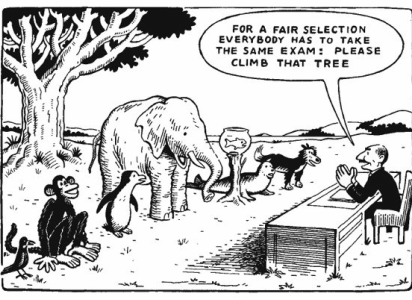

That changed slightly in 1926, with the introduction of the SAT, which evolved from an Army IQ test and supposedly tested for “innate intelligence.” The SAT helped even the playing field, narrowing down applicants from white males to intelligent, academically capable white males.

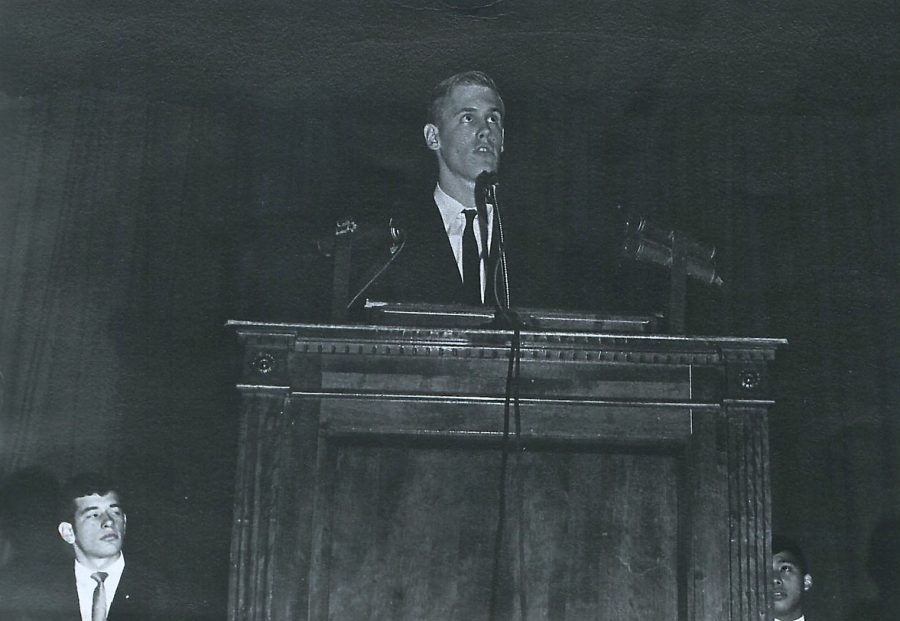

In 1964, James Pennington was officially the first Black student to attend Yale, which catalyzed the desegregation of the other Ivy League schools. With more applicants, the acceptance rates for Ivy League universities began to slowly decrease. By the 1960s, Brown University had an acceptance rate of 73%. From there, it would only get harder to get into any Ivy League, especially as most colleges began to open their doors to women.

Princeton was the first Ivy to accept women, admitting its first cohort of 101 women in 1969. This opened the floodgates of applications for white women, pushing acceptance rates down to around 50%, as other Ivies followed Princeton’s lead. Women of color also began to be admitted to other Ivies in 1975.

Once Ivy League Universities were open to all, offered financial aid, and genuinely considered each applicant, instead of relying on parental donations, the applicant pool grew exponentially, creating the ultra-competitive Ivy League admissions processes today.

Now, the acceptance rate for every Ivy League University is under 10%, with the majority of them under 5%. Harvard had the lowest rate at 3.2% as of 2022, and Cornell had the highest rate at 7.8% in 2023. To be admitted to an Ivy League, applicants must have near-perfect GPAs, extremely high SAT/ACT scores, diverse and well-rounded extracurriculars, and a well-written personal statement, along with multiple supplemental essays for each Ivy.

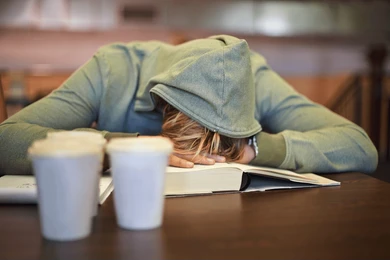

There are, of course, stories of some exceptional students who get into every Ivy, but even if an applicant meets all the demanding criteria, admission is not guaranteed. Every would-be Ivy aspirant has heard the horror stories of valedictorians slaving away for the perfect GPA, test scores, and extracurriculars – only to be rejected by their dream Ivy League university.

While Ivy Leagues no longer solely consider familial ties, with some, such as MIT, outright banning legacy admissions, there are still applicants who are accepted based on their legacy status (according to Naviance), only increasing the exclusivity of these prestigious institutions.

At Brooklyn Tech, around 700 students from the senior class apply to Ivy Leagues every year, with only around 100 students offered admission. Even so, the true number of attendees may be considerably lower because some students get into multiple Ivies, and some acceptances are turned down due to financial situations.

According to a poll conducted by The Survey, 53% of respondents stated that the reason they were applying to Ivy League schools was for the reputable name they confer on graduates. Mr. Ip Ken, guidance counselor for prefect N, said “Reputation is definitely one reason dozens of students apply, but it’s not the main reason.” Indeed, a vast majority (38%, according to Naviance) of Tech graduates attend CUNYs and SUNYs.

For Architecture major Mary Bhowmik (‘25), who is currently applying to Cornell, the pressure is very real — not only for her, but to all 1560 seniors at Tech this year.

“I’ve spent all of high school preparing for these next few months,” she said.

Despite her diverse extracurricular activities and high GPA, Bhowmik worries about the strength of her application.

“It’s actually terrifying to think that even a perfect SAT, with perfect grades and perfect letters of recommendation, might not be enough,” she said. “And if that’s not enough, where does that leave me?”

Many seniors share Bhowmik’s concern. Since Tech is such a rigorous school, students can be very competitive, always vying for another internship or a bit of extra credit, but a select few have an advantage over most applicants.

Legacies are an extremely controversial aspect of the college admissions process, which 62% of respondents to The Survey’s poll agreed were unfair. As colleges and universities around the country gradually ban legacy admissions, most Ivies have been slow to fully embrace the trend.

Social Science Research major Celine Deng ‘25, who is applying to multiple Ivies, questioned legacy as an admissions criteria.

“I don’t understand why some students get priority just because their parents went to a certain school,” she argued. “Your parents don’t show who you are as a student or a person.”

With the Supreme Court’s recent ruling against affirmative action in cases brought against Harvard and the University of North Carolina, and more schools going test-optional, the college admissions landscape continues to shift. For Tech seniors, these changes are nerve-wracking.

“I know some schools are going test-optional, but that just adds to the confusion,” Deng added. “I worked so hard for my test scores, but now I’m worried they won’t matter as much.”

The college admissions process is bound to continue changing as standardized tests become digitized and the applicant pool expands, but one thing is certain: Tech students are sure to continue sending in those applications, despite tanking acceptance rates and skyrocketing standards.