On the last day of the 2023-24 school year, former NYC DOE Chancellor, David Banks, suggested the possibility of a citywide school cell phone ban for the beginning of the 2024-25 school year. At the time, he explained that a decision would be finalized in two weeks and confidently announced that, “[The DOE is] very much leaning towards banning cell phones.” A few weeks later, in response to the Chancellor’s statement, Mayor Eric Adams stated that the city was not ready, and thus would not implement the ban until at least the 2025-26 school year.

Since then, the Chancellor has swung back and forth on the topic. In his last statement, on September 12th, he said that the New York City Health Commissioner’s Office was conducting a study on cell phone use and effective prevention methods, but ultimately a ban would be “the mayor’s call to make.” Since Banks’ resignation and Adams’ indictment, the ban’s prospects have become even more uncertain.

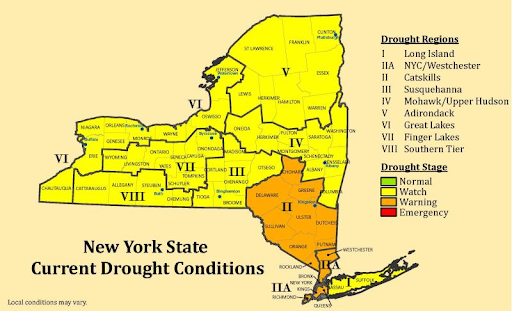

On the state level, New York Governor Kathy Hochul has also promised to detail a plan for cell phone prevention in January 2025, at the start of the next legislative session. Last summer, she conducted a “listening tour” where she heard the perspective of NY students, teachers, and parents regarding cell phone usage in schools. This information, she says, will be used to inform her proposed legislation for the ban.

Jonathan Haidt is a sociologist at NYU, Tech parent, and the author of New York Times bestseller The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Haidt’s work has brought to light many of the harmful effects social media has on adolescents today, and he is a strong proponent of a DOE-wide cell phone ban.

“There is a growing understanding that smartphones, social media, and addictive algorithms are incompatible with adolescent development,” he commented in a sit-down with The Survey. His work has amplified the social media conversation, ultimately bringing the issue of cell phone use to New York legislators’ desks.

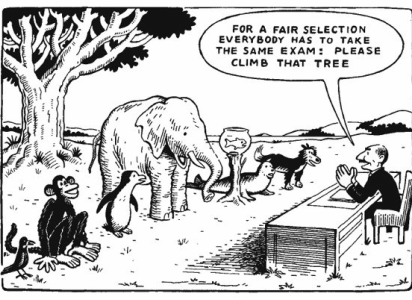

In The Anxious Generation, Haidt argues that the “phone-based childhood” must end, citing statistical evidence such as the skyrocketing rate of mental illness and anxiety, which has doubled in teenage girls in recent years, as well as the decline of test scores that have been consistently dropping since 2012, as soon as iPads and Chromebooks were widely introduced into classrooms.

“There is a consumer product that is killing hundreds of children a year, sickening tens of thousands a year, maybe we should ban the product,” Haidt asserted, expressing concern about smartphones and social media. “For some reason, in the online world our attitude is, ‘well, what are you gonna do about it?’” Haidt responded to the mayor’s comment regarding the city’s readiness with some thoughtful advice. “I am sure that they will do it [ban phones]. I would suggest that they do it for the fall of 2025 and that they find some money to support schools that can’t bear the expense on their own.”

Some students are already a step ahead of any ban. Physics major Jameson Butler (‘25), a self-described “luddite” who chose to give up her smartphone a few years ago, finds that her academic life is much more successful without it.

“It’s made doing my school work and paying attention in class so much easier,” she explained. “I no longer define myself by my ADHD like I used to, because my smartphone was making that a lot worse.” Butler clarified that, like any student, she has procrastination habits, but not being able to “pull the phone out of [her] pocket and distract [her]self” has made it a lot harder to put things off.

Butler has seen personal benefits from cutting smartphone use out of her life, but unlike Haidt, she is unsure that it would be possible to implement the DOE-wide cell phone ban at a school as large as Tech.

“I dont think it’s feasible,” said Butler, imagining that it would take too much time to secure every student’s phone and that it “would have to be someone’s full-time job.”

Will Treece, an AP US Government and AP Comparative Politics teacher at Tech, expressed similar concerns. “I sympathize with the goals of the policy…but I have huge questions about enforcement and implementation,” he explained.

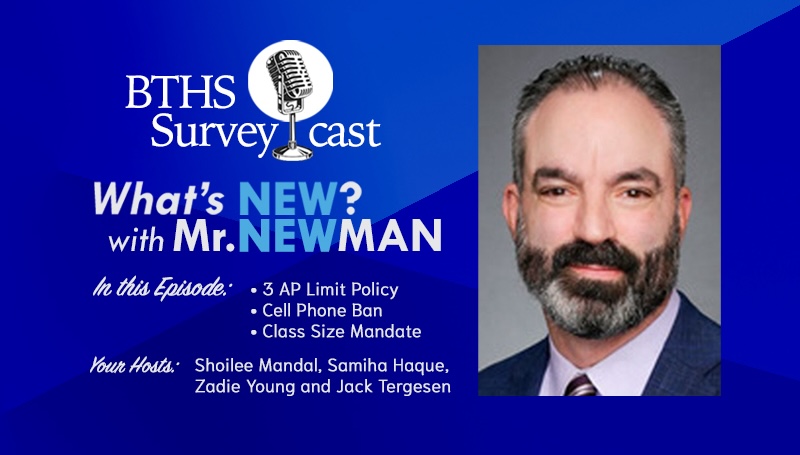

A recent Survey poll revealed that 96% of Tech students do not support a DOE-wide cell phone ban. Principal David Newman joins the overwhelming majority of students in questioning the policy, which he would feel hard pressed to authorize on his own at Tech.

“It would have to be some decree from above,” he said. “If there’s an option for me to decide to ban cell phones at my school, I am not going to do it.” For now, he said, schools are only being strongly encouraged to implement bans and there is no specific policy for citywide bans on the table.

Many schools in NYC, and across the state, have already implemented independent bans. One of the most popular methods these schools have adopted is the use of Yondr pouches. Yondr pouches are magnetically sealed fabric pouches that, according to NBC news, 41 states have spent $2.5 million on over the last eight years.

Kaya Jackson (‘25), a student at Clinton High School, detailed her experience with her school’s partial cell phone ban. At Clinton, 6th-10th graders must store their phones in Yondr pouches at the start of the day. “Think of it like a wallet,” suggested Jackson. “Each student has their own and it’s not something that stays at school, they take it with them back and forth.” The pouches are locked and unlocked by a “masterkey” magnet that is placed near the entrances and exits of the school.

While Yondr pouches are largely effective in stopping the usage of phones in class, no system is flawless. “They cause delays in entrance time and an unnecessary amount of disturbances from notifications that cannot be silenced once the pouches are locked,” commented Jackson. At Tech, even minor delays in entrance time have large repercussions. With a Yondr pouch system, what was once just a chaotic first day of school or a spontaneous metal detector day could become a permanent reality.

Lastly, Jackson feels that the policy has shifted the energy of her school’s student body. “It’s made kids sneakier,” she said. “They use decoy phones and people started discovering that if you banged on the lock hard enough it would release.”

Another common concern with the cell phone ban proposal is that, with gun violence in schools on the rise, many parents are worried about not being able to contact their children in an emergency. While Haidt shares and understands this concern as a parent, he suggested that if there were a real emergency, “school security experts are united in saying that what you want is for the kids to be quiet and follow directions. What you don’t want is all the kids pulling out their phones and crying to their parents.” Simply put, he said, “I think that we need to do what’s best for the kids, not our feelings.”

With the recent mayoral scandal, and Chancellor Banks stepping down, the future of a cell phone ban remains in uncertain hands. Regardless, as trailblazers like Jonathan Haidt continue circulating data about the harms of cell phone use and children, the place of these powerful devices in the classroom is likely to change.