The growing industry for artificial intelligence (AI) has opened doors in the world of technology, working to match human-like abilities and accomplish tasks more efficiently. However, Rebecca Ramnauth (‘17), an impressive Brooklyn Tech alumna, has different plans for AI.

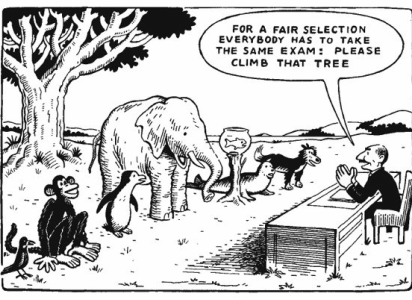

During her time at Tech, Ramnauth was a part of the Software Engineering major, pursuing her passion for computer science through Advanced Placement (AP) courses and major classes. However, Ramnauth said, “[she didn’t] think Tech gave [her] enough exposure in the technical courses, like AP Computer Science.” Ramnauth feels that she needed a class to push her abilities beyond coding languages, leading her to ask herself questions such as, “What does it mean to make [AI] efficient?”

After graduating from Tech, Ramnauth attended Long Island University (LIU) and majored in computer science, hoping to continue on the path she began in high school, but at a different pace. Ramnauth found herself with a lot of downtime at LIU, which was a big change from the many 40-minute periods seen throughout the school day at Tech.

“Very quickly I realized I [couldn’t] do the two-hour lecture, four-hour break,” she admitted. “I decided to take a lot of courses to fill up my attention span. I needed more material to study. Before I knew it, I was taking [up to] 60 credits a semester…That was my loophole.”

Ramnauth began her freshman year at LIU with 34 transferrable AP credits from her time at Tech, which, combined with her first-year coursework, earned her 128 credits for her Bachelor’s degree, as well as 64 for her Master’s degree in computer science by the end of her first year of college.

Ramnauth explained, “I didn’t go into [college] with the aim of finishing early.” She credited the rigorous coursework at Tech, saying “[It] played a big part in [her] willingness to read a textbook” during her time as an undergrad.

Although short, Ramnauth’s time at LIU was not easy. “Some things I had to compromise on,” she said. “There are the three S’s: study, social, and sleep. You have to pick two out of the three and mine, for sure, was studying — the social part meant studying — and then sleep.” However, she continued, “I wouldn’t recommend it to people because there is a lot more to college that you can benefit from.”

Beginning her junior year at Tech, Ramnauth spent three years working for Con Edison as a software engineer, a position she had received through Tech’s internship program for CTE majors. As she was searching for other job opportunities, Ramnauth realized “[she] didn’t like the big tech industry world because corporate goals [weren’t] exactly what resonated with [her].”

Ramnauth’s younger sister was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), motivating her to focus her studies on serving a social good. “Watching my sister grow, and some of the struggles she faced really did shape the course of my research,” she emphasized. Ramnauth found herself less interested in the passive and traditional coding she learned through her experience at Tech and rather wanted to focus on creating technology that could not only help her sister, but also others facing similar struggles.

When applying for jobs after graduating from LIU, Ramnauth said employers “didn’t believe [her] resume.” In the summer of 2018, she went back to LIU and taught three courses over two semesters as an Adjunct Professor of Computer Science, one of which was a graduate course. She also became the Assistant Dean of Research for another two semesters following her time as an adjunct professor.

With this experience, Ramnauth was able to narrow her interests and realize she had a passion for teaching computer science. However, to gain more experience, Rmnauth knew she had to earn her PhD.

When Ramnauth was applying to graduate school in 2018 following her time as a faculty member, she was drawn to deeper questions about computer science. Using elements of her work from the Advanced Placement (AP) Research class she took at Tech, Ramnauth wrote her Master’s Thesis on Artificial Intelligence (AI).

“I [wrote] about how AI could be useful for social reasons rather than what traditional AI looks like and that’s figuring out algorithms and a better way of mapping probabilities together,” she recalled. “I was thinking more about how we answer all these questions but for social good,” she said. Her thesis led her to continue on the PhD track in Social Robotics at Yale University beginning in 2019.

As Ramnauth explained, there are different categories of AI, each seeking to achieve something different. Ramanuth’s goal was to contribute to social robotics in a way that did not describe robots as “dull, dirty, and dangerous.”

“[My coworkers and I] are designing robots that have interactions…that are actually exciting and interesting and can hold the attention of a child more than a toy could,” Ramnauth noted. “Those were some technical challenges that I would not have come across in traditional computer science.”

One of her lab’s first studies utilized a robot called Jibo, originally developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Ramnauth and her team added AI functionality such as naturalistic gaze and speech. Jibo worked to engage in eye contact with children with ASD. Avoidant eye contact is a “diagnostic hallmark” of the condition that can make social interaction an intense challenge.

Jibo’s main function in this study took place within the home. With this robot, children are set up with a gaming screen to focus their attention while sitting next to a parent. The robot passively follows the child’s attention until eye contact is made. The robot then diverts its “attention” to the parent and then back to the child, encouraging practice.

The robot was implemented into homes for the study in 2020, around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, but was continued and observed over several weeks. Impressively, Ramnauth was able to collect significant results from the experiment.

This application of Jibo was one of the first studies that gathered significant data on the effects of robotics on children with ASD. Although it is said that non-verbal behavior such as eye contact is not meant to develop before months of exercise, Ramnauth’s study was able to defy this. “We saw real meaningful change in kids as young as six years old from all ends of the spectrum with very similar improvement only after two weeks, and this was within my first year at Yale,” she noted.

With the success of this first robot, Ramnauth was eager to keep her work focused on social good. “It was immediately socially rewarding for me,” she remembered. “Here I’m running code for actual people on a real system that is physically embodied in your home that you are interacting with and you’re hoping that it helps your child in some way, and it does. To get that result and that data was so cool!”

Ramnauth’s studies branched out beyond supporting children with ASD, ranging from elders with dementia, teenagers with anxiety, and people with clinical depression. With her sister now an adult, one subsequent project involved developing “small talk” skills vital to so many interactions in adult life, from job interviews to dating scenarios.

AI is just as challenged by small talk as many humans are. “Small talk is something that ChatGPT and all of these large language models are really bad at,” Ramnauth mentioned. “They’re good at giving you information and persistently asking if you need help with anything.”

Using Jibo as her platform, Ramnauth saw results similar to her ASD study. Adults with ASD were quickly becoming more comfortable in quick exchanges.

Other notable robots crafted with Ramnauth’s help, such as VectorConnect and Ommie, have also targeted social skills in developing elementary schoolers and anxious college students, respectively. Ommie was one of the first robots Ramnauth built from scratch while VectorConnect was originally bought as a commercial product and edited for research functionality. Ommie worked on breathing exercises while VectorConnect helped keep young children socially active during the pandemic. Although these robots have yielded positive results, questions remain about the qualitative difference between AI and real person-to-person interactions.

“[Children] have all kinds of social and interactive play that [they] wouldn’t get with a formal teacher teaching you [school] material,” Ramnauth noted of VectorConnect. “I think robots fall on the spectrum of sociability. On one end you have these toy-like objects and on the other end, you have more human-like robots that can have eyes and ears and can move around. You can modulate where on the spectrum where you want a robot to fall.”

Given all the AI technology Ramnauth has been able to create with the help of her undergraduate students and other researchers, she is inclined to earn a PhD so that she can spend the rest of her career teaching, running her own research lab, and making technology like her robots more accessible.

Ramnauth is also continuing to show that AI has a fundamental role in aiding those with ASD and similar conditions. Although she has no interest in starting her own company, she is still looking for ways she can contribute to making this type of technology more cost-efficient and affordable for consumers.

Ramnauth acknowledged how far she has come in her research. “The thing I’m most proud of saying is that I have to come up with these research questions and make sure the project is feasible.” However, she noted her work is not done. “Being able to pave the path for other AI researchers would be a goal,” she said.