Myanmar vs. Ukraine: White Focus in the Media

May 3, 2022

“We saw a flagrant violation of international law,” U.S. President Joe Biden announced in a press conference, a few hours after Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24th.

That same day, the topic of Ukraine and Putin was trending #1 on Twitter, with a combined thread of over 5 million tweets. On a much smaller scale, the Social Studies department of Brooklyn Tech decided to have the teachers design mini-lessons following the invasion. While some teachers chose to do something smaller, others used the opportunity to advance their curriculum. Mr. Stevens commented that his Participation in Government class spent an “entire week” studying the Ukraine invasion. “By now, all of my students are experts,” he added.

Overall, public outrage and shock from the classrooms of Brooklyn Tech, to social media, to world leaders were palpable.

The only ones seemingly not shocked? The people of Myanmar (Burma) — and for good reason. In the context of decades of an extremely violent, devastating civil war and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, it might feel difficult to stomach the sudden outpouring of shock over the Ukraine invasion.

Just two days before Russia invaded Ukraine, the Associated Press reported that thousands of Burmese civilians were targeted, injured, and forced to leave their homes by Myanmar’s military airstrikes. The United Nations’ refugee agency reported that in the last week of February 2022, an estimated 42,000 Burmese people were forced to flee their homes. The violence was in the wake of last year’s coup, wherein the military proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, launched a full-scale coup d’etat on Myanmar’s democratic party: Myanmar’s National League for Democracy (NLD).

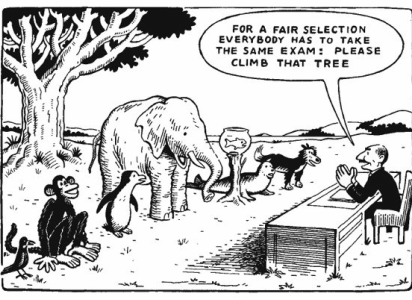

So, why didn’t President Biden mention Myanmar in the State of the Union, the same way he did with Ukraine and Russia? Why didn’t the History Department at Brooklyn Tech demand a mini-lesson on the ethnic cleansing of Myanmar, like with Ukraine?

The reality is that this situation is a prime example of social media and Western support, especially U.S. aid, coming down to proximity to whiteness. In Myanmar, those being ethnically cleansed by the government are brown Muslims. In Ukraine, the majority of the victims are white. Authoritarianism and human rights disasters, according to the West, are only newsworthy if those being attacked look a certain way. Look no further than the vitriolic public reaction to Muslims in the U.S. after 9/11, when Islamophobic hate crimes rose by 1617% from 2000 to 2001.

One Muslim Tech student, Abdul Mohamed (‘24), expressed disappointment over the wide support for Ukraine in school, compared to the lack of acknowledgment of multiple crises in South Asia and the Middle East. His own home-country, Yemen, has also faced multiple human rights crises and war crimes in the past year, which have also been only loosely covered by Western media. “There were over one million people killed in Iraq, as well as crises in Yemen and Syria,” he said. “It’s sad that it took until the Ukraine invasion for people to take notice.”

Mohamed summarized that “No one seems to care about Muslim ethnic cleansing in Myanmar or the conflicts in the Middle East, but suddenly with Ukraine, it’s an ‘emergency.’”

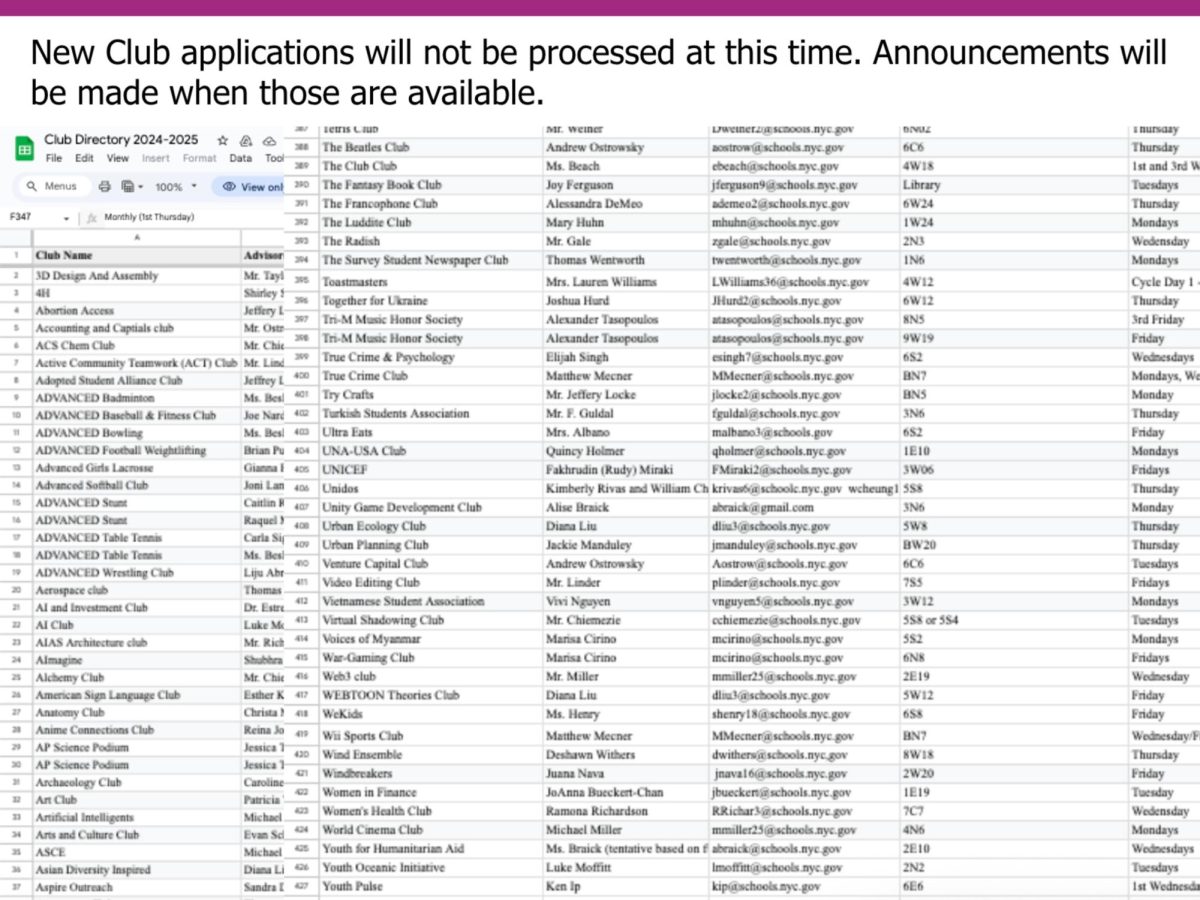

Similarly, a recent poll of 93 randomly selected Tech students found that only 11% would consider themselves aware and/or minimally educated about the Myanmar crisis, while 89% said they would not. The reality is that we cannot expect Tech students to be educated on history and ethnic cleansings if it is expunged from their sources of information.

Following the events of late February, the Bangkok Post reported that #RespectOurVotes, #HereTheVoiceOfMyanmar, and #SaveMyanmar were all trending on Twitter within the country. Yet, for worldwide Twitter trends, it took less than twenty-four hours for all mentions of Myanmar to be completely erased from the Top 50. Despite a lack of international support, Burmese activists persevered via social media, until Twitter and Instagram were temporarily restricted post-coup by the government. Without their voice, advocates against the military coup on social media and in the public eye have become virtually non-existent.

The human rights community in Myanmar, on the other side of the world, has taken note of a Western lack of support. Chit Min Lay said, “Since the Bush Fellowship, there has been minimal support from America and other countries, even in Asia.” Lay, now a well-known Burmese activist and a former leader of the 88 Generation Students group, is a Burmese former political prisoner. He was arrested at the 1996 and 1998 Yangon student protests and was sentenced to thirty-one years in prison, released more than a decade later in 2012.

His American wife, Polly Dewhirst, used to work as Senior Project Manager for transitional justice at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation in South Africa, but has now been an activist for the Rohingya in Myanmar for almost a decade. “We know that we have little outside help,” she said. “Since Ukraine, social media and people outside of the Burmese human rights community spreading even a fraction of that awareness for Burma would be incredible.”

There has also been a stark difference in how we accept immigration. On March 24th, 2022, U.S. President Biden announced plans to accept 100,000 Ukrainian refugees, following the Russian invasion.

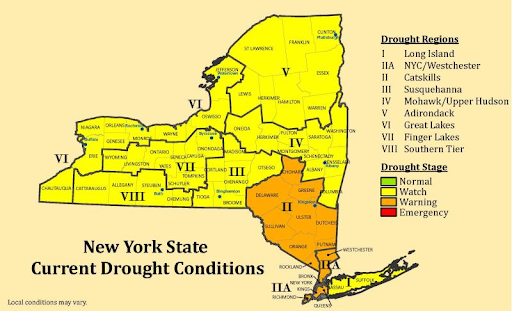

Compare that policy to the former U.S. President Trump’s 2018 travel ban, which heightened travel and immigration laws for citizens of Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen — all of which are predominantly Muslim countries. In 2020, Trump added six more countries to the list, one of them being Myanmar — for which he also specifically banned U.S. immigrant visas from being issued. As a result, very few Burmese people immigrate to America and to New York.

Still, Brooklyn Tech has one of the most diverse Asian populations in the city, with an existing — although small — Burmese student population. One of these Burmese students is Brooklyn Tech Su-Nanda Win (‘24). “I still have family in Myanmar,” she explained, “and it has been extremely scary for everyone.” She described the paranoia and fear her family in Myanmar experienced doing normal daily activities, even before the coup: going out for groceries, communicating with her parents, and turning on the lights, due to frequent power outages. “People my family know or were friends with have died due to the military,” she said.

Of course, one country’s crisis does not discount another’s. But awareness disparity can.

“Whenever I mention my parents are from Myanmar, no one has ever recognized it as a place they’ve ever known or learned about,” Win explained. “Just because it isn’t directly affecting [Americans] like with Ukraine increasing gas prices, doesn’t mean it should be talked about any less.”